Eyes and glasses

Eyes have always fascinated humans. They acquired metaphysical properties in antiquity, from” The Eye of Horus” which was used by ancient Egyptians to protect its wearer from evil, to classical Greek mythology which related how seeing the mythical gorgon’s face meant being turned to stone. Vision is central to awareness and consciousness. Modern neurophysiology shows that the optical cortex has many connections throughout the cerebral cortex to explain the deep integration of vision into emotions, memory, sensations and language.

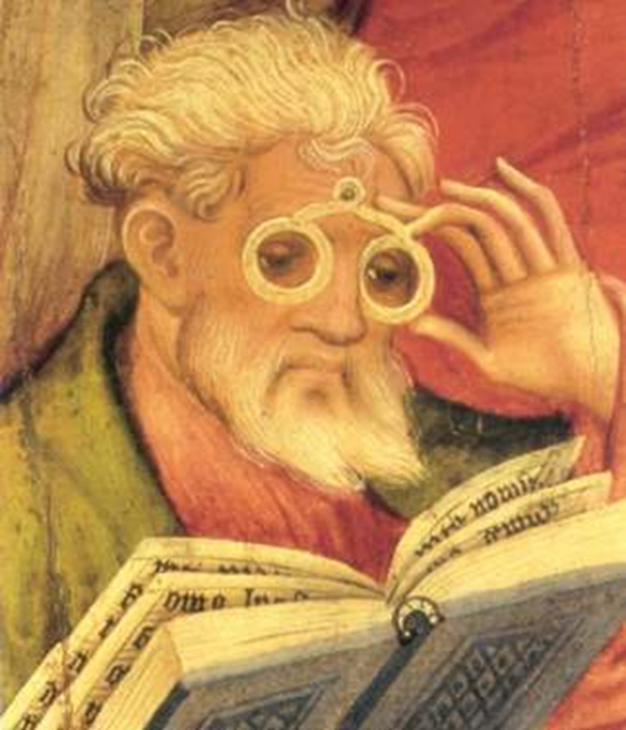

Poor vision affects many humans, so it is unsurprising to find that there have been frequent attempts to improve human vision across history. Whilst myopia or short sightedness arises in childhood, presbyopia or the diminishing ability to focus on objects at close range affects us all in our fifth decade. As the development of reading and writing in the classical periods of both Asia and Europe progressed, so to did vision related problems and the need for corrective lenses. References in texts are sparse which makes it difficult to trace the development of spectacles. Claims have been made around the world from China, India, Africa, Arabia and southern Europe though they are often found to be erroneous or added later to ancient texts to establish precedence. It is likely that spherical clear quartz stones obtained magnification for wealthy Egyptians in pharaonic times and Emperor Nero was said to use an emerald to see better in 60 CE. Protective eye covers were recorded in China and Inuit used them to reduce snow blindness. Widespread use of magnifying tablets and stones by scribes and monks was found in the twelfth century but the lack of understanding of the behaviour of light on reflective and translucent surfaces prevented consistent progress. The Byzantine philosopher and mathematician Ptolemy (100-170 CE) studied optics and recognised magnification was obtained by looking through transparent spheres and spherical flasks filled with water but he did not master the laws determining reflection, refraction or chromatic aberration. His written accounts travelled East and were used by Islamic scholars, including Alhazen in his Book of Optics ca. 1021. It seems likely that the origins of modern spectacles are first to be found in thirteenth century Italy. Records from Venice (especially from Murano) suggest that the glass makers’ skill allowed them to make spheres accurately and magnifying convex lenses quickly followed. Whether these were made by blowing a hollow flask and using a section of it as a lens or by cutting the lens from a block or bisecting a solid sphere and then grinding and polishing with serially finer abrasives is unknown because the glass makers’ techniques were kept secret and were strongly controlled by their guild to create a monopoly for such valuable inventions. It is likely that all these methods were used. Giordano of Pisa wrote in 1306 of it being not 20 years since eyeglasses had been made but the idea of joining two lenses into a frame to make spectacles took time. The earliest examples of rivet spectacles were found in Celle in Germany dating from 1400 and the first spectacle shop opened in Strasbourg in 1466. Trade in lenses was extensive and widespread by this time and included a shipment of 24,000 Italian glasses found in Turkey dating from the early 1500s. These predated the earliest authenticated pictures and references in China or India.

The renaissance, the enlightenment and the demands of industrialisation accelerated the process and success was rewarded with improved efficiency, advances in scholarship and prolongation of the working life of artisans. The invention of the printing press in 1456 was pivotal in eyeglass history and improved lamp-making extended the working day. With the widespread printing of books, the use of reading glasses began trickling down through the ranks of society. However, it was not until 1620s in Spain that the problems of making graded lenses were overcome, allowing the prescriber to test the eyes and match the lens required. The study of optics and technical advance has resulted in improvement and demand for visual aids into the 21st century.

(wikimedia.org: Conrad von Soest)

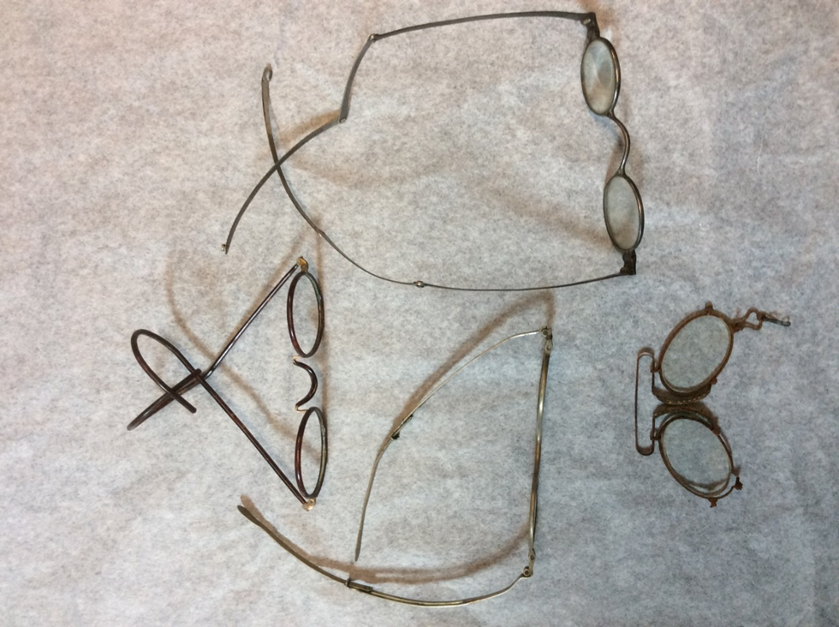

It took until ca 1750 for Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in the Netherlands (1632-1723) to make the first compound microscope. He used both hollow and solid spherical lenses as the objectives, but he had to make them himself to enable him to be the first to see various microbes and cells. Roger Bacon knew about concave lenses for myopia in 1262 but an explanation was not forthcoming until Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), more famous for his astrological discoveries and elucidating the laws of planetary motion, published his work in 1604 on optics, Astronomiae Pars Optica, though his interest in vision was secondary to astrology and astronomy. He outlined the laws governing the behaviour of light, reflection and the principle of a pinhole camera but the law of refraction was absent from his work. Cylindrical lenses used for strabismus were not designed until 1825 when they may have been introduced by George Airy a British astronomer contemporaneously with John McAllister in Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) is said to have introduced bifocals by using half-moons of convex and concave lenses to correct his myopia and presbyopia but this was probably an English invention by Samuel Price in 1775. However, George Washington is credited for helping to reduce the prejudice that glasses indicate frailty by using them to read part of his speech to rally his troops who were on the point of mutiny in their encampment near New York in 1783. This was widely reported, and they responded with sympathy to his situation by withdrawing their complaints. In London, in 1727, Edward Scarlett made spectacles held comfortably in place with arms passing over the ears which slowly replaced monocles, pince-nez and lorgnettes. These continue to be improved using tough, light, alloys to make resilient frames with emphasis on comfort, personal image and fashion.

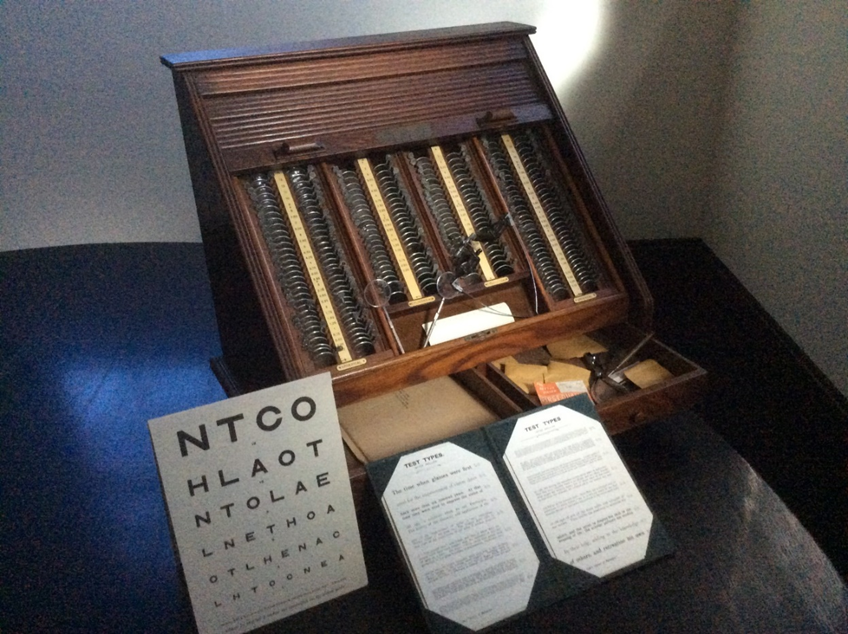

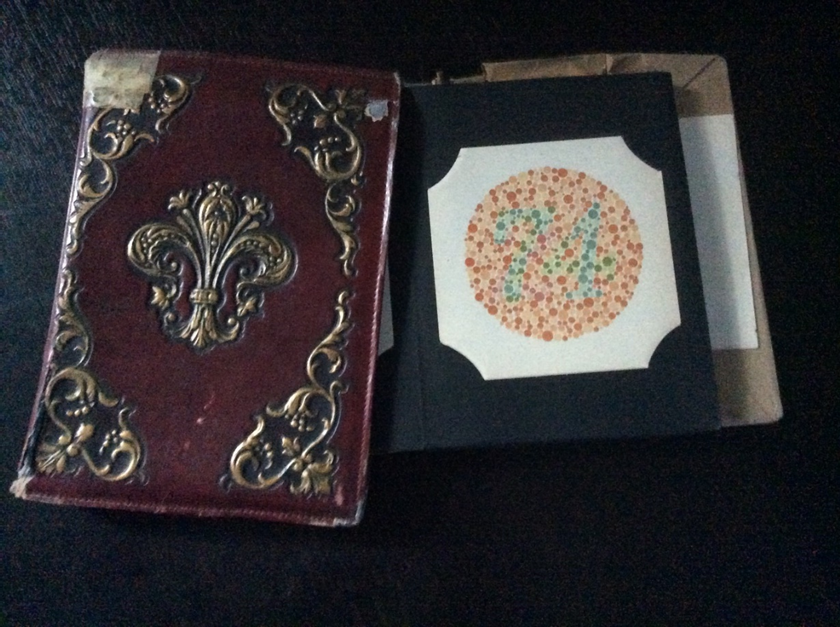

Further major developments came with the Zeiss and Moritz Von Rohr spherical point-focus lens in the early twentieth century. Plastics replaced glass from the 1960s after acrylic from the 1940s was found to be too brittle and yellowed with age. Television heralded a huge demand for distance vision correction in the 1950s. Testing of visual acuity and prescription of glasses was carried out by a variety of providers including doctors opticians and pharmacists using a variety of lenses and other aids such coloured dot charts to demonstrate colour blindness and manually measuring existing lenses.

Used by Dr R Parker and Donated by Dr Chester Wilson from Longreach

The discovery of high refraction, durable plastics together with glare reducing polarisation encouraged thin, safe modern spectacles and allowed light, fashionable frames. Contact lenses and corrective surgery have made inroads into the need for corrective vision aids, but spectacles retain most of the market. An adjustable corrective lens was produced by Joshua Silver in 2008, using silicone and a syringe to alter the lens curvature but this has not been widely accepted. Like many technological histories there is no clear trajectory of the development of these everyday items with a story full of numerous small improvements and many contentious claims.

The development of licensing and training of the providers of spectacles also seems to be somewhat haphazard. The dispensers of spectacles from an optical prescription are called opticians and doctors were frequently responsible for testing and prescribing lenses and pharmacists sold them. Much of this association was unregulated. Surgeons and physicians specialising in eye treatments call themselves ophthalmologists and often work with opticians for refraction impairments and before lens implants, after lens removal for “ripe” cataracts, but their speciality was primarily for the study, diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the eye. However, many general practitioners also continued to test eyes and prescribe lenses and pharmacists still sell reading glasses directly to their customers.

Optometry as a profession arose from non-medical optical specialists and prescribers of corrective lenses. Whilst existing for centuries it was not until the latter half of the 20th century that these professionals became systematically regulated. They have slowly separated from other health care providers but in a few European countries such as France and Italy and in some states in the USA, they remain unregulated. In this country, they are governed by the Optometry Board of Australia and are self-regulating under the auspices of the Australian Health Practitioners Regulation Agency. To celebrate the Australian College of Optometry’s first 75 years, Professor Barry Cole wrote “A History of Australian Optometry” in 2015. Orthoptists originally only treated eye movement disorders but for many years their university-based training has involved them in other fields such as strabismus amblyopia, diplopia and low vision disorders amenable to therapy through eye exercises. It is noticeable with training and organisation the professions tend to extend their remit supporting the tendency towards fragmenting health provision into more compartmentalised and specialised fields. (1408)

The most useful account I found was in the History section (4.1) in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glasses#Precursors) which includes appropriate references and links also:

https://www.optometryboard.gov.au/News/2015-07-21-media-release-protected-titles.aspx

A History of Australian Optometry; Barry L. Cole; The Australian College of Optometry, 2015 ISBN 978064937922

The Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History aims to celebrate Queensland’s medical history by telling the stories of its people, events, objects, scandals and triumphs. We welcome all stories with a medical history aspect. Get in touch with us at medmuseum@uq.edu.au.