Out of laboratory testing

Posted by Robert Craig

Up to 50 years ago biochemical and haematological testing was not easily available for referral from practitioners outside hospital laboratories. Most office and home pathology testing are now done using various commercially available testing strips which include a large variety of urine and blood tests for biochemistry, pregnancy testing and recently a test for the presence of Corona Virus as well as the widely used test for faecal occult blood for screening for bowel cancer. However, this technology was not available until about 1960 and the Museum has many objects from that time. Other laboratory testing was often more expensive or unobtainable to clinicians working outside major hospitals, but haemoglobin estimation was widely practised using a variety of proprietary haemoglobinometers based on colourimetry matching the sample against a standardised scale.

The Museum has many urinometers (hydrometers made to reflect the range of specific gravity of urine) which are useful in determining the capacity to concentrate urine for patients with renal failure. This commonly occurred as a result of complications (glomerular-nephritis) from streptococcal infections (untreatable in the pre-penicillin era and called Bright’s disease). Microscopic examination of the urine was a common side room practice to demonstrate cells (leucocytes) or crystals such as uric acid as well as the presence of bacteria with Gramm’s stain. Glucose was detectable using Fehling’s or Benedict’s solution depending on the colour change from the reduction of blue copper salts to red copper oxide which could be confirmed by tasting to distinguish it from other sugars and aldehydes! Urine albumin measurement for diagnosing nephrotic syndrome and pre-eclampsia of pregnancy was done by adding reagent (picric and citric acid to a measured amount of urine enabled estimation of albumen using an Esbach’s Albuminometer).

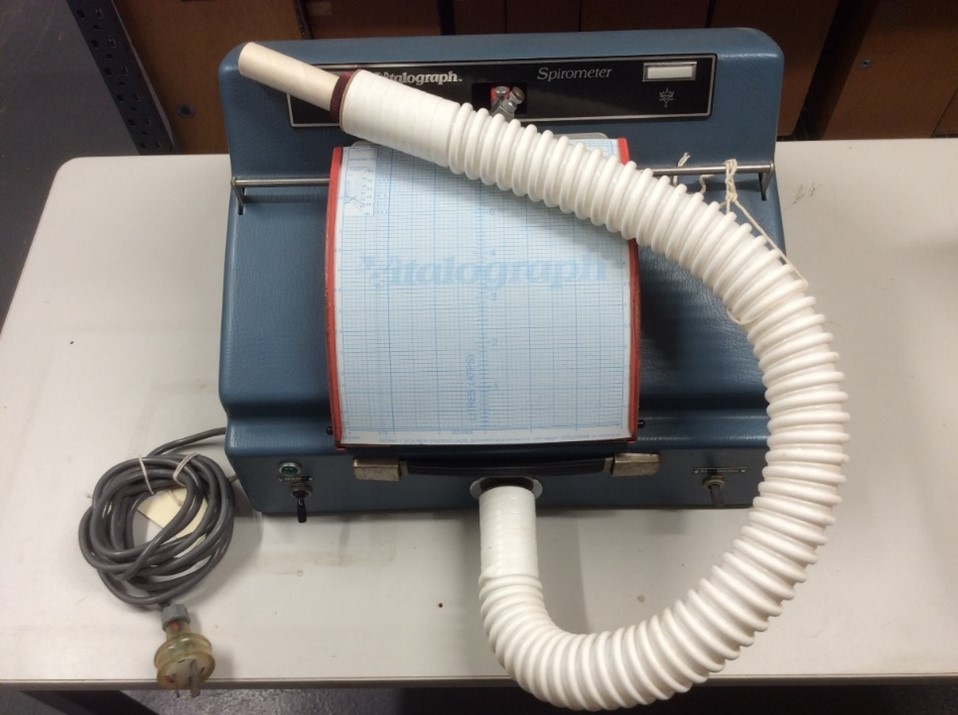

Further equipment commonly found increasingly through the first half of the 20th century, in addition to sphygmomanometers and microscopes, were portable ECG machines, spirometers for pulmonary function testing and later peak flow meters.

The Vitalograph Spirometer could measure Vital Lung Capacity and forced expiratory flow in one second. It didn’t take long before small plastic instruments were produced for individual use, these often being given as promotional gifts to General Practitioners by bronchodilator manufacturers to enable serial and home measurements of the therapeutic effect of their pharmaceutical preparations and to advertise their products.

These items have been modernised beyond recognition and have become increasingly redundant with patient self-monitoring and internet connections to enable distant interpretation of results which has been particularly useful for the interpretation of electrocardiographs from out-of-office portable machines. The widespread availability of pathology collection centres has enabled rapid, automated, accredited testing and efficient transmission of results has reduced the need for out of laboratory testing but the ease with which it can be obtained has probably added to the huge increase in pathology testing along with the exponential increase in health costs. The sophistication of sphygmomanometers has matched the other testing equipment but simple to use, inexpensive devices have been made available for home use.

Many earlier practitioners were multiskilled and less dependent on specialist services. Martindale’s Bacteriological Testing Case from about 1900 (pictured) illustrates this point being a comprehensive bacteriological kit including multiple stains slides and equipment to culture swabs taken from patients. During World War I some medical officers in forward emergency stations were instructed to be prepared to culture stool specimens to differentiate typhoid fever from paratyphoid because these infections were causing so much debility. Typhoid fever was well known, and troops could be immunised though the duration of the illness and its complications were more serious than the more recently recognise outbreaks of diarrhoea caused by S. paratyphi. The case pictured is on display at UQ’s IPLC (Integrated Pathology Learning Centre). It includes slides and laboratory equipment in the one box. The contents would be sufficient to carry out the testing required of those medical officers but accuracy of results would be open to doubt. The advertisements on the lid refer to Martindale’s related products; a urine testing kit, a burette stand and a uric acid testing kit.

All photographs are of objects from the Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History collection, with the exception of the image of handheld lancets, courtesy of The Lancet journal.