Where there’s a will there’s a way: Queesland’s first instance of the mechanical ventilation of a small child

A story from Dr John Hains (Anaesthetic Registrar RBH 1966-67)

In the early 60's, children with stridor or serious chest infections were admitted to a medical ward where there were beds with facilities to increase humidity and oxygen concentration. These were plastic tents which covered the head of the bed much like a mosquito net. The ward was near the operating theatre in case the patient's condition deteriorated and they required an urgent tracheostomy.

This procedure had evolved from the era when diphtheria was prevalent. The successful immunisation program had virtually eliminated diphtheria, yet the alarm was sounded at 8.30am each morning as a reminder of time past but was viewed as an indication to residents that it was time to start work.

At midnight on the 29 April, 1966, the daughter of one of the medical staff, a little girl aged nine months and weighing 19.5 pounds (8.84kg) was bought to the Children's Hospital with a severe cough and rapid respiratory rate. The following morning, she was placed in a steam tent but there is no mention in the chart of any diagnosis. (The original chart was destroyed when the hospital was transferred but a copy had been made so all timings can be authenticated).

1/5/66

She was formally admitted by the deputy superintendent (Dr John Eckert) who was concerned enough to notify the superintendent (Dr C.Fison). A throat swab taken at the time showed growth of staph aureus and E.coli which were sensitive to Streptomycin and Chloromycetin.

Medically the child's condition is deteriorating even though the medical staff are wanting it tto improve. By 2pm. Fison records that "the child is wearing out and needs relief". By 3.30 she has had a tracheostomy under general anaesthetic. The smear had been examined and Chloramphenicol was prescribed. At 7.45 John Eckert records she is still restless and tachypnoeic though at 10.30 pm she is recorded as sleeping with a good colour and respiration not laboured.

2/5/66

She looked restful but was refusing to eat so tube feeding was introduced. As well there was a problem with the tracheostomy tube so at 9.30am she was returned to theatre where this was corrected, and thick pus was aspirated. The anaesthetists were so worried that the director (Dr. Beric Jackson) slept the night in the flat under the ward.

3/5/66

At 10am she was pumped gently with an "oxygen bag" with some improvement which was not maintained when this was ceased. She was transferred to the adult Respiratory Unit. The tracheostomy tubes used at this time were silver and consisted of an outer curved trochar which could be tied in place and an inner tube which could be removed for cleaning or replaced with one of similar size. There are numerous examples of these in the Museum. The disadvantage of these is that they were not sufficiently airtight to allow the lungs to be ventilated. There were no commercially available disposable paediatric tracheostomy tubes but there were red rubber Oxford curved endotracheal tubes.

4/5/66

At the morning review it was noted that the liver was displaced downwards and medially and her condition had deteriorated markedly. Chest Xray confirmed that there was a right tension pneumothorax with collapse of the right lung. A chest tube was inserted and the lung re-expanded. She still had difficulty breathing.

Paediatric anaesthetist Dr. David Jackson modified an Oxford tube (cut 4cms off the tip) and used this to replace the silver trachy tube. By using taper tip connections this could be connected to the T-Piece used to ventilate children during an anaesthetic. Manual ventilation was begun in the afternoon with anaesthetists taking it in turns as this was quite tiring. In between spells, David began fiddling with a Radcliffe ventilator not in use at the time. This was a simple machine with an electric motor which was used to drive a clover-shaped wheel which lifted a weight and let it fall again which connected to a bellows would ventilate the lungs. This produced a tidal volume much larger that required for a 8.5kg child whose estimated tidal volume would be about 60ml. Using a 2-litre expiratory bag he constructed a dummy lung in parallel and adjusted the resistance so the child received approximately 90 mis per breath with the rate set at 20/minute. There was no method of measuring the tidal volume other than a Wright's spirometer which measured the expired volume over a number of breaths and then calculated the tidal volume at 90 mis.

5/5/66

Dr. Jackson stayed with the child during the night and reported there had only been one problem due to secretions and debris blocking the tube.

6/5/66

Despite improvement in the clinical situation and Chest X-ray attempts to take her off the ventilator were not successful and it was decided to wait another day.

7 /5/66

At 8am it was decided to again give her a trial off the ventilator. There are no times mentioned in the chart but the last entry of the day at 8pm. "there is a large cyst in the lower R lung and the patient continues to breath spontaneously". She continued to improve though there were serious problems with the chest drain and secretions blocking the tracheostomy tube. The intercostal drain was removed on 11 May 1966 and the tracheostomy on 16 May 1966. She was transferred to Fraser ward on the 19th and discharged on the 21st.

Although some larger children were ventilated in an "iron lung" during the polio epidemic, this was not possible with small children with serious lung disease. I believe this was the first child to have mechanical ventilation of the lungs in this state. Her survival was due to a number of factors including her high profile, the resilience of her parents, excellent nursing and the best medical attention available at the time.

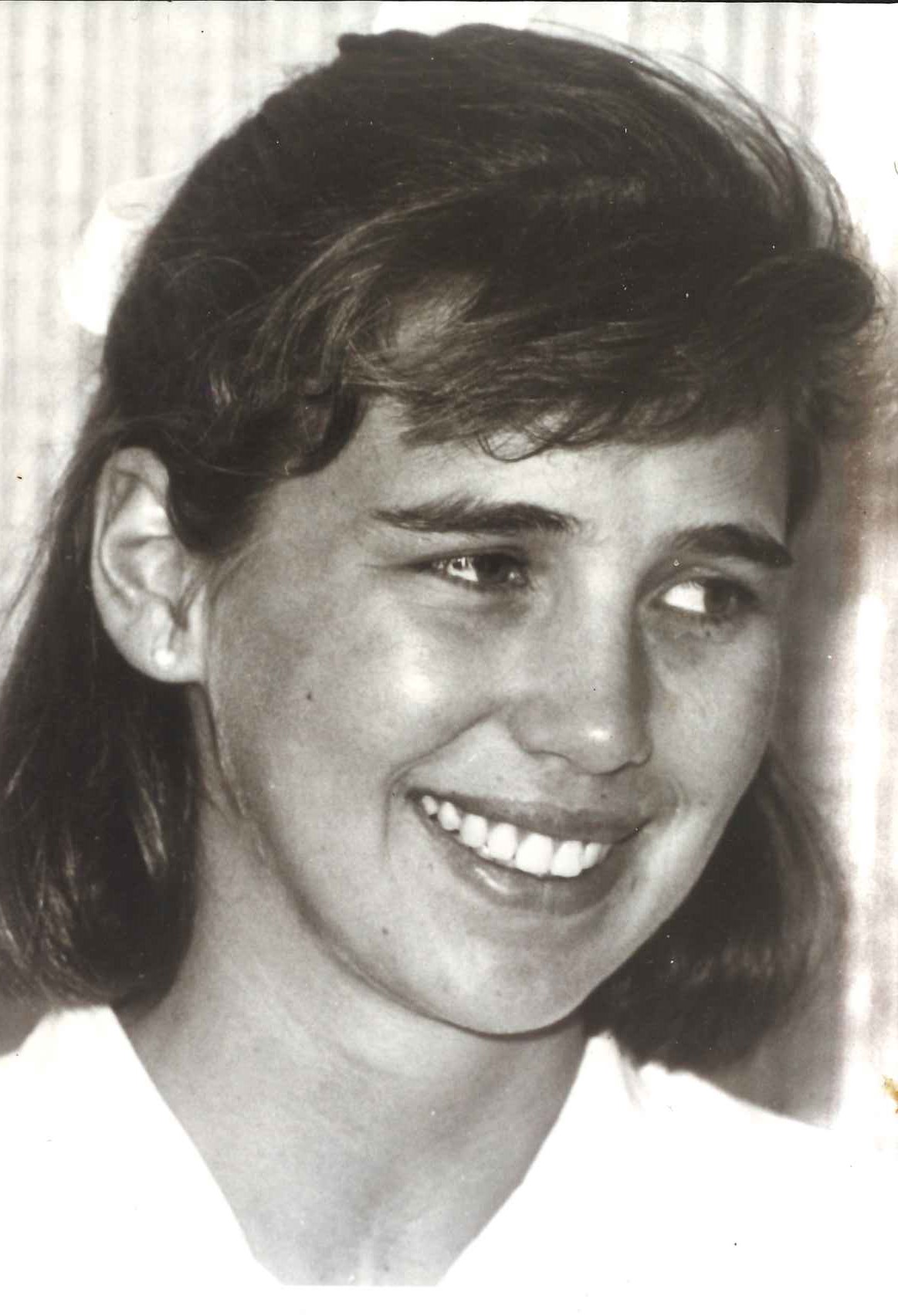

Despite this harrowing beginning, the patient is living a full and happy adult life with three children of her own (Personal communication).