Dominique de Andrade, The University of Queensland; Cheneal Puljević, The University of Queensland; Kerri Coomber, Deakin University, and Peter Miller, Deakin University

This is the third in a series of articles discussing a recently released comprehensive evaluation of the Queensland government’s 2016 policy reforms to tackle alcohol-fuelled violence and the implications for liquor regulation and the night-time economy in Queensland and Australia. A summary report is also available.

A disturbingly high proportion of young people, particularly women, experience unwanted sexual attention in entertainment districts across Queensland.

This is the bad news from a two-year, independent evaluation of the Queensland government’s 2016 “Tackling Alcohol-Fuelled Violence” (TAFV) policy (the good news included a significant statewide reduction in serious assaults).

Read more: Lessons from Queensland on alcohol, violence and the night-time economy

One in three patrons reported unwanted sexual attention – including harassment, unwanted touching, or sexual gestures – in or around a licensed venue in the preceding three months. Among those who reported unwanted sexual attention, two in three women (68%) also reported physical and/or verbal aggression.

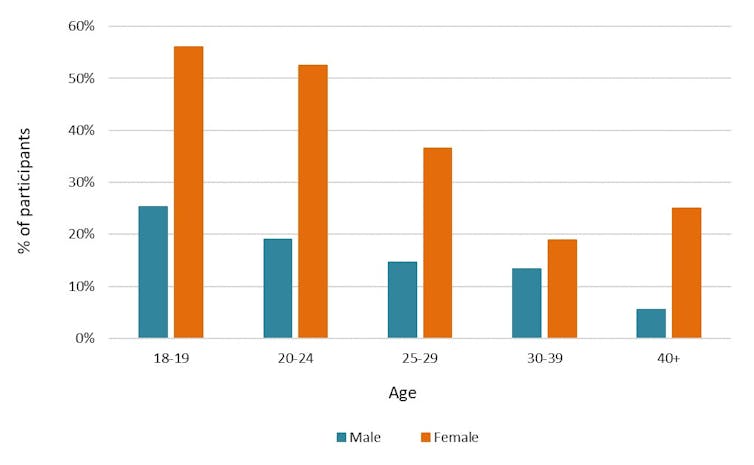

The rate of unwanted sexual attention was highest for young women (ages 18-24). More than 50% had experienced this harm in the previous three months, as the chart below shows.

In the Fortitude Valley entertainment district, a staggering one in four reported unwanted sexual attention on the night they were interviewed (26% of 262 female patrons interviewed and followed up the next day).

Over the two-year evaluation, 4,055 patrons (43% female) were interviewed on Saturday nights on the streets of three entertainment districts – Cairns, Fortitude Valley (Brisbane) and Surfers Paradise (Gold Coast).

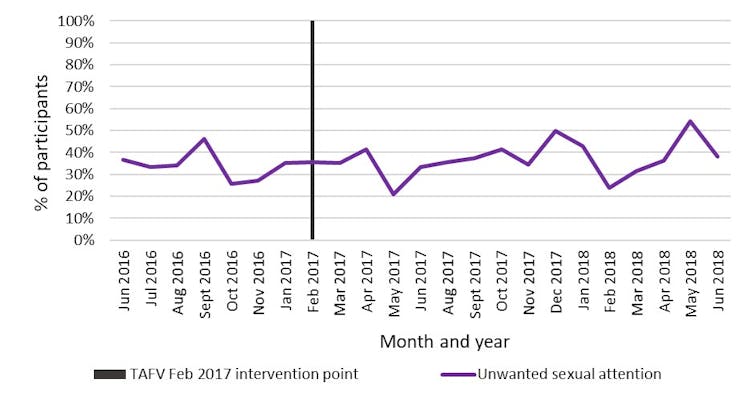

While the rates fluctuated over time in these areas, the rate of unwanted sexual attention didn’t change when comparing the months before and after the TAFV policy took effect. The chart below shows the trend for Fortitude Valley.

Uncomfortable truths

These findings highlight some uncomfortable truths.

First, the unwanted sexual attention young women experience in the night-time economy is an intransigent public health and safety problem.

Second, the issue is considerably under-researched.

Third, overcoming the problem requires discussion beyond alcohol accessibility and drinking practices.

The findings of the evaluation sit against a backdrop of increasing global intolerance of the sexual abuse and harassment of women. For example, the number of women reporting sexual assault to Queensland Police has increased for the past six years. This increase might be attributable to the raising of public consciousness (e.g. the “Me Too” campaign).

Read more: #MeToo has changed the media landscape, but in Australia there is still much to be done

Such awareness-raising has had impacts on broader social norms around sexual aggression towards women. But the evaluation suggests this messaging has largely failed to permeate the social norms of the night-time economy.

Why haven’t nightlife norms changed?

Understanding and addressing the mechanisms behind unwanted social attention in this context is particularly challenging. In addition to the broader social norms, licensed venues have their own cultural norms – including sexualised environments and heavy drinking – that often contribute to unwanted sexual attention.

Recent experimental research suggests unwanted sexual attention in these settings may be related to males misperceiving the social environmental cues. They read alcohol presence, alcohol consumption and revealing dress by females as signs of sexual interest. They might have been influenced by decades of sexualised alcohol marketing.

Such research highlights the need to better understand the risk and protective factors affecting victims and perpetrators of sexual aggression, and how these factors interact with cues in the physical environment.

Responsibility is broadly shared

These findings have many implications for policy and practice.

For a start, many experiences of unwanted sexual attention sit beyond the boundaries of the law. This raises a number of questions. Who is responsible for acting on unwanted sexual attention in and around licensed venues? And is it time to reassess the individualisation of responsibility in entertainment districts?

One strategy that attributes some responsibility to venue staff has been trialled in cities such as London, Chicago, Vancouver and Melbourne. The Good Night Out initiative aims to train and empower licensed venue staff to act as capable guardians (instead of bystanders) who intervene in incidents of unwanted sexual attention. While theoretically such approaches are promising, the evidence for such targeted strategies remains limited.

The pervasive problem of unwanted sexual attention in night-time economies also requires attention from local and state governments. Strategies that specifically address this harm should be embedded in alcohol policy.

Without a more sophisticated approach that targets all types of aggression, young women will likely continue to experience high rates of unwanted sexual attention on their nights out.

Read more: No harm done? 'Sexual entertainment districts' make the city a more threatening place for women ![]()

Dominique de Andrade, , The University of Queensland; Cheneal Puljević, Research Fellow, Centre for Health Services Research, The University of Queensland; Kerri Coomber, Research Fellow, Deakin University, and Peter Miller, Professor of Violence Prevention and Addiction Studies, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.