Doctor’s Bags

Doctor’s bags have been around for as long as doctors have consulted with their patients when away from their own premises or clinic.

This has probably been for as long as anyone can remember, but it seems that it wasn’t common practice until the post enlightenment era of science-based medicine and safer surgical procedures.

In an era of rising costs with rapid changes in technology and aseptic procedures, it is again becoming a less usual arrangement; some would say to the detriment of a doctor/patient relationship, creating an unequal balance of power when the patient is always in the “doctor’s territory”.

The scene in the Netflix series the “Crown,” where major surgery is performed in Buckingham palace is unlikely to occur again.

Within the Museum’s collection, we have a selection of bags, instrument boxes and medicine chests.

The first I will show you is a small leather Gladstone bag, sold as a midwifery bag suitable for obstetric forceps, basic delivery equipment, a local anaesthetic set, and vapour inhalational anaesthetic equipment for ether or Chloroform, commonly used in the first half of the 20th century.

Illustrated below is a much larger leather Gladstone bag (500mm x 250mm x 300mm): Dr Harry Foxton’s medical bag containing many surgical instruments which was gifted to the Marks Hirschfeld Museum by his family.

There were three doctors in the Foxton family. Dr Harry Foxton began the medical practice in Cleveland in the early 1900s and the contents of the bag reflected his special interest in ear, nose and throat surgery. The bag contains tonsillar snares and guillotines, various E.N.T. instruments, including a variable pitch tuning fork, as well as a Politzer acoumeter with mastoid chisels and nasal bone forceps.

The instruments were mainly manufactured from 1910 to 1930 but included items used in ophthalmology anaesthetics and bronchoscopy, with several instruments for laryngeal procedures. Also included was a pair of obstetric forceps and general surgical instruments dating up to the 1950s. It was a family collection rather than one doctor’s “tool kit”.

The capacious strong leather Gladstone bag with brass fittings and a calico lining was much larger than what would be needed for domiciliary visits, unless significant home surgery was anticipated (which was not an unusual occurrence for the early years of this century). It is more likely though that the bag was used to transfer personally owned instruments between the various hospitals and clinics, probably pre-sterilised and wrapped in suitable sets for convenience and to save time.

Pictured below is a Regimental Medical Pannier from 1943, probably from the New Guinea battlegrounds, which was used by the Australian Army and has a well-preserved list of (former) contents stuck on the lid.

It is likely that this had been used previously in other campaigns. The arrangement of the contents of these baskets had not been changed substantially since the Crimean War in 1850, though the items included kept up with the needs of contemporary medicine.

A similar pannier with its contents displayed is illustrated on the London Science Museum website which shows the contents in 1915.

Army first aid knapsacks were designed for battlefield use by stretcher bearers and other ‘medics’ and would have contained emergency wound dressings, bandages and a tourniquet for stopping bleeding, together with morphine squeezable containers with needles incorporated into them for ease of injections for pain relief.

The picture below illustrates a standard 1950s black leather doctor’s bag with drawers. This one has a special provenance as it belonged to Air Vice Marshal, Glen (‘Bill’) Reed, who was director general Air Force Health Services (1984-87). His family provided the Museum with historically significant items from the Apollo moon landing when Dr Reed was an RAAF medical professional involved in the Australian monitoring station in 1969.

Some Other Examples of Special Medical Containers

A Travelling Medicine Kit with Materia Medica from about 1850 is one of the antique items in the collection. It contained the following basic ingredients:

- Croton Oil to treat constipation

- Ipecacuanha to induce vomiting for poisoning and other stomach ailments

- Ergot, for uterine haemorrhage and unwanted pregnancy

- Valerian for anxiety and insomnia

- Lead Acetate, Copper Sulphate to treat skin infections and irritations

- Antimony, Calomel containing mercury for more systemic infections, especially gonorrhoea and syphilis

- Blistering Fluid for poultices as well as raising blisters for rheumatism, bodily aches and pains

- The gallic acid was likely to have been used as an astringent tonic maybe with valerian as a calming agent

Surprisingly, Morphine or laudanum were not included but were probably expected to be freely available for diarrhoea and pain relief. It should be noted that traditionally diarrhoea was viewed as a healthy reaction to toxins and the recommended treatment to ‘the flux’ was strong laxative to clean the bowel (Armstrong’s “Diseases Most Fatal to Infants” 1767)

Burroughs Welcome Tabloids and Syringe Kits were patented by Burroughs Welcome, in about 1910, for the use of their patented tabloids which contained a standardised dose of soluble preparations to be injected after dissolving in distilled water. This meant that it was easy for practitioners to carry them without resorting to preparing the injection from stock in a dispensary.

It was not until much later that pharmaceutical manufacturers prepared sterile injections in sealed glass ampoules. The larger tabloids were for oral use, to standardise dosage and probably were an important factor in the replacement of the doctor’s traditional ‘bottle of Medicine’ with the introduction of a more rational approach to therapeutics.

For 50 years or more, cartridge syringes were popular for use with local anaesthetics, especially in dentistry, until the recent introduction of prefilled disposable syringes. Kits with changeable glass cartridges like the tubes containing needles illustrated below were used in emergency situations.

There were a range of agents available which included adrenalin, coramine and anti-arhythmic agents. The fixed dose together with the ease of reloading the syringe made them especially user-friendly and safe.

As RFDS boxes were prepared by the Royal Flying Doctor Service for use by non-medically trained carers in isolated stations and settlements. Any responsible person could use the contents as instructed by radio telephone from the RFDS base medical and nursing staff by reference to the index list of systematically organised medicines and equipment which were regularly updated.

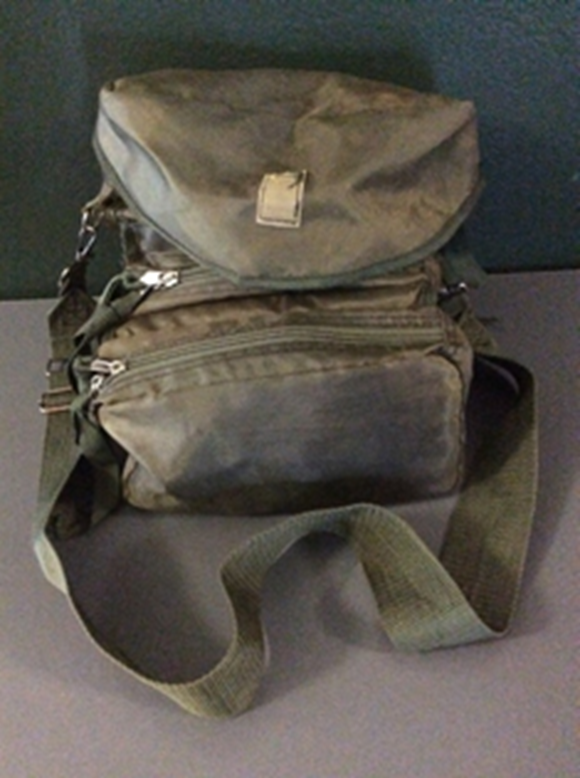

On a personal note, I have included my first aid and emergency kit when working as a rural GP from Crows Nest District, just North of Toowoomba. In 1984 the nearest ambulances were Oakey and Toowoomba, often 50 km or more from isolated farms and country road accidents.

The equipment was complemented by a personal selection of PBS emergency drugs (27 commonly needed drugs, in different formulations, to use in emergency situations and offered free to prescribers through the pharmaceutical benefits scheme). I kept a diagnostic set in a ‘tool kit’ box with i-v giving sets and bags of saline or other suitable solutions for fluid replacement in situations of catastrophic bleeding, together with a disposable laryngoscope, airways to meet the needs of road traffic accidents and industrial accidents as well as for such situations as hypoglycaemic coma in a milking parlour. Nowadays, a portable defibrillator would be needed but wasn’t then affordably available.

In conclusion

These bags and boxes provide much background to the practice of medicine over the last 200 years. The last UQ Museum newsletter discussed the beautiful lancets for cutting infants’ gums, now long gone from the also forgotten waistcoat watch chains of many doctors.

Many of the instruments and medicines illustrated in this article are now obsolete and electronic connecting devices for the measurement of vital signs to a specialist centre are now a reality to enable an isolated health worker (often not a doctor) to get almost instant expert advice on patient management.

However, in a search online for doctor’s bags, there is no shortage of offers on sale. From small attaché and Gladstone bags, made from leather fabric and soft plastic ($200-400), to much larger containers with multiple compartments or fold-outs reminiscent of a tradesman’s tool box ($5-600), and a Salvatore Feragamo fashion item advertised as a doctor bag for $3,000!

It would seem doctors still require specialised bags to reinforce their status to patients and transport their equipment, even if the rate of home visiting has declined precipitately in recent years. This may be a feature of increasingly casual employment for doctors working at several different clinics during a week.

The Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History aims to celebrate Queensland’s medical history by telling the stories of its people, events, objects, scandals and triumphs. We welcome all stories with a medical history aspect. Get in touch with us at medmuseum@uq.edu.au.