Book Review: The history of inoculation and vaccinations; Lecture Memoranda Australiasian Medical Congress Aukland, N.Z. 1914

Published for Burroughs Wellcome & Co products, summary by Robert Craig

I came across an attractively illustrated, cloth-bound promotional booklet in the Marks Hirschfield historical collection, some time ago. It seems particularly appropriate to include it in this Newsletter when so much is being discussed about seeking an immunisation for COVID-19.

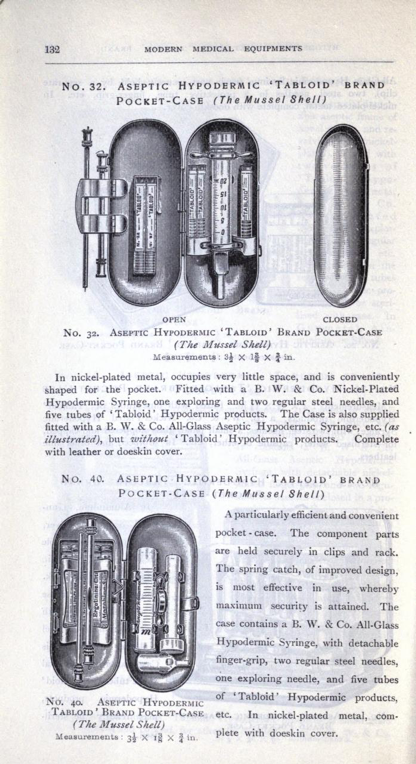

Information from Joanne Maddocks at the Wellcome Library, Euston Road London NW1, about these publications revealed that during the early years of the company, Henry Wellcome was very keen to promote his company at Medical Congresses. He produced several similar booklets, that combined information on the history of medicine (often specifically on the region where the Congress was held) with details on Burroughs Wellcome & Co products. This is demonstrated by the inclusion in this edition of extensive advertising for portable medical kits, including ‘Tabloids’ as provided to Arctic and Antarctic explorers and aviators, as well as the call for standardisation of medicines into brand products such as tabloids, phials etc.

Most of the book is devoted to the history of inoculation but there is a further short chapter on the cultivation and standardisation of ‘Galenicals’ in a ‘Modern Physic Garden – maybe to encourage the cultivation of Australasian herbal remedies?

Ancient and pre-enlightenment practices are outlined with many classical and anthropological references. European and British experience is detailed and includes an account of Empress Catherine II of Russia, promoting inoculation by importing Dr Dimsdale from England to inoculate herself and her family; as well as the story of Lady Mary Montagu, wife of the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Court in 1717, who widely disseminated the Turkish practice of “ingrafting” during autumn.

However, these practices depended on transferring virulent smallpox (from a patient’s pustule in various forms) to a recipient whom they tried to protect through good diet, rest and sometimes bloodletting. Inevitably, there was a significant mortality and morbidity, but the procedure was protective from future infection. At the time, there was vigorous debate about the rights and wrongs of inoculation with reports of practitioners and patients being physically assaulted for their participation. Whilst abortive attempts were made to reduce the virus’s virulence, it was not until recognition that infection by Vaccinia from cowpox (a single lesion seen on milkmaids’ fingers and cows’ teats) protects the patient from Variola, the infecting agent in smallpox. There are many anecdotal reports about the efficacy of cowpox vaccination from the time of Charles II (1660-1685), but a well-publicised case of a Dorset farmer, Benjamin Jesty - who inoculated his wife and three of his children in 1774 - is credited with initiating the proven safe use of the procedure and the protection of the recipients. The first medical man to report on Vaccinia vaccination was Edward Jenner (1749-1823) from Berkley, Gloucestershire. He was a young apprentice surgeon in Ludlow when he became aware of the protective effects of cowpox. Jenner took up the challenge of researching this issue when he gained influence as an assistant to the famous Dr John Hunter in London. In 1789 he used another variant of pox, swinepox, to inoculate his own son with success. In 1796 he carefully documented experiment where he used cowpox to vaccinate a healthy eight year old, James Phipps, and, after the scab had healed after two months, he demonstrated that James was immune to inoculation with smallpox. A further three cases in 1797 enabled him to submit a paper to the Royal Society which was rejected as “not strong enough to warrant publication.” However, in 1798, he privately published a paper titled “Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease discovered in some of the Western Counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of Cowpox.”

Although resisted in some quarters, with the patronage of Lord Egmount and the Duke of Clarence, there was rapid promulgation of the method. Austria, Italy, France, Spain and North and South America were using the method by 1799. This was especially promoted when the then President, Thomas Jefferson, supported the first vaccinations being carried out in 1800 in Massachusetts. Napoleon Bonaparte received direct petitions from Jenner and released specified prisoners even though France was at war with Britain at the time. The same happened in Spain and Austria; clearly an indication that the fear of the scourge of smallpox outweighed the usual protocols of hostilities. The speed of the global take up of this innovation is staggering.

There were strong campaigns to discredit the practice but, in 1802, A Jennerian Institute was created and Edward Jenner was granted ₤10,000. This reflected the public health imperative for free vaccination with Vaccinia. He was given a further grant of ₤20,000 in 1806 with support from the government, the Crown and the Royal College of Physicians. However, he became exhausted from fighting repeated attacks on his work and character and returned home for good in 1814 after his wife’s death. He died aged 73, of a stroke in 1823 (a year after the birth of Louis Pasteur). However old habits and misinformation die slowly, and it was not until 1840 that the dangerous practice of using small pox exudate for Variola inoculation was decreed illegal.

There are three brief final chapters: Firstly Pasteur’s efforts to find a partially successful vaccine for rabies (1889); Koch’s influence on bacteriology and his work on anthrax prevention through sterilisation and his unsuccessful attempts to treat tuberculosis with tuberculin; Finally Haffkine’s, Kolle’s, Ehrlich’s and Ferran’s cotemporaneous work on cholera, diphtheria, tetanus and plague, together with the use of serum for treatment. Development had been slow and patchy following the success with smallpox vaccination in 1800. It was to require another 150-160 years of research to better understand immune responses to eradicate smallpox and enable comprehensive immunisation from childhood diseases. This little book provides striking examples of how difficult it is to predict how medical “breakthroughs” will translate into relatively safe clinical use.