Medicine’s inventors and innovators

Discoveries in medicine are often represented as if they were the result of a progression of experimentally validated building blocks of knowledge. If this were true it would follow that significant advances should come from those in possession of most information, but this thesis does not allow for the ‘Eureka’ moments of insight.

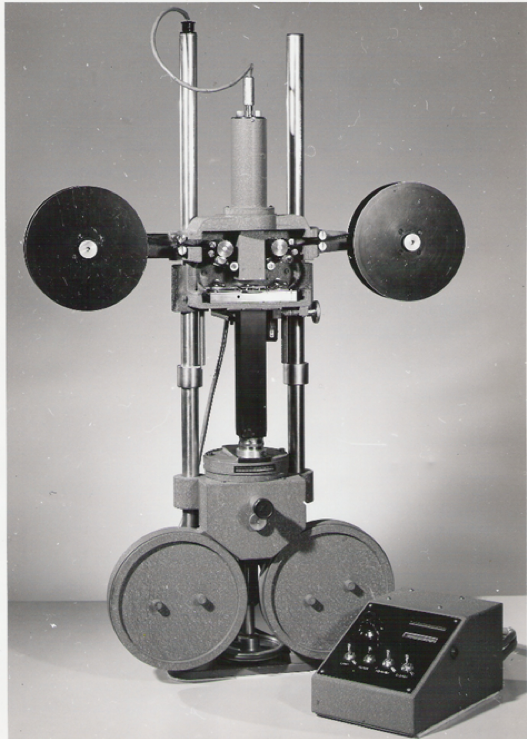

Serendipity is often responsible for the spread of new ideas: The Sunday Mail of January 17, 1999 carried an article headlined “Monster of an Idea; Doc’s Brainchild grew into IMAX.” The article is about the invention of an innovative piece of film equipment developed by an engineer, Ron Jones, for Dr Jim Hood who in 1965 received a grant from the National Heart Foundation to develop a special cinematic Xray to study heart abnormalities.

The results of the collaboration between Dr Hood and Ron Jones was a “Rolling Loop” Projector in which the film rolls continuously on a drum transport mechanism. The invention was applied to the project, and an example of the invention is held in the Marks Hirschfeld Museum. However, the story does not end there. Three Canadians were working on preparing a large format multi-screen film which they were to show at the Osaka Expo in 1970. They were interested in the film transport invention of Ron Jones and visited Australia to preview it in operation at the Eldorado Theatre at Indooroopilly. They purchased the concept for their invention and the group was to become IMAX Corporation.

An article in the ANZJ of Surgery (Mark D. Stringer and Omid Ahmadi; ANZ J Surg 79 (2009); 901-908) draws attention to a number of important discoveries initiated by students and inexperienced scientists.

In the 20th Century, notable examples were the identification of Heparin by Jay Mclean, when he was still a medical student in 1916. Thomas Fogarty conceived a balloon catheter for embolectomy (and urinary catheters) as a medical student, but probably had the initial idea in the early 1940s when he worked as a surgical scrub technician. Frederick Banting and Charles Best collaborated to identify the therapeutic potential of an extract of pancreatic islet cell for the treatment of diabetes in 1921. For the first time ever, within a few years of the commercial preparation of insulin, a diagnosis of Diabetes Melitus was no longer the death sentence it had been since the recognition of the disorder. Banting was a medical student who had deferred his studies to serve in WW1 and Best was a recently qualified doctor.

Some earlier examples include:

- Auguste-Maurice Raynaud (1834-1881) identified the syndrome of severe episodic vasoconstriction of digital vessels with pain, and sometimes localised gangrene, when he was 28 and writing his doctoral thesis.

- Paul Langerhans (1847-1888) made two discoveries when a student under the tutelage of Rudolf Virchow, with his description of the dendritic cells (or tissue macrophages) of the skin, as well as the islet cells in the pancreas later to be shown to be the endocrine gland in the pancreas, which produces insulin.

- Augusta Klumpke (1859-1927 from San Francisco) started her career in neurological research in Paris where she was permitted to take up medical training. As a student in 1877, she elucidated the origins of brachial plexus palsy and its association with Horner’s syndrome. Even after winning an Academy of Medicine prize, it took intense lobbying to persuade the medical establishment to accept her application to be the first female intern in Paris in 1886.

- Ruggero Oddi (1864-1913) studied the function of the sphincter at the distal end of the common bile duct as a fourth-year medical student at Perugia, a university unable to award medical degrees. He moved on to Bologna where he continued to research the importance of the sphincter to the digestive process, but his career ended in ignominy after accusations of drug use and professional misconduct.

On some occasions, the lack of seniority has delayed the acceptance of some discoveries, as defined by Szent-Gyorgyi. The identification of the antibiotic properties in penicillin in 1897, should rightly be attributed to Ernest Duchesne (1874-1912) from Lyon, and William Clarke in 1842 in New York; described the earliest administration of ether as an anaesthetic. Both of whom were medical students at the time. The earliest example cited in this article was of Johan Ham who, while a medical student in Leiden in 1677, identified spermatozoa in semen and was able prove the need for their presence for conception. He went on to hypothesise that for fertilisation to occur the spermatozoa had to penetrate the ovum.

For the most part, the success of a young scientist in establishing credit for a discovery was fraught with difficulty – not least because of the claim of more powerful senior researchers. Oliver Sacks met this difficulty, which he outlined in his autobiography, “On the Move”. When writing his research on the clinical findings and use of dopamine in the treatment of late onset extrapyramidal symptoms - following patients who’d suffered from the 1920s epidemic of encephalitis lethargica - the director of the institute where he worked claimed the research as his own and dismissed Sacks.

Intuitively, it has seemed to me that the era of such discoveries has passed with the increasing expense and complexity of biomedical research. However, an article by Trent Dalton in the Weekend Australian Magazine; March 7-8th; 2015; 20-25, contradicted this opinion. Ideas for a revolutionary artificial heart germinated in a young Gary Timms, who formulated the problem in as a plumbing engineer. Conventional medical preconceptions and preoccupations would have inhibited his motivation and perseverance to create the BIVOR; a rotary, bi-channelled pump with only one moving part and no bearings to wear out. Translation studies are still not complete for this invention, but it has always been the case that the full potential of a medical discovery can take many years to realise, fail to attract financial or critical support or even slide into obscurity. The prime requirement is always “to think what no one has thought before” and whether it is Johan Ham in Leiden in 1677 or Gary Timms in Brisbane in 2004, it is often a young person without prejudice and preconceptions who can come up with the unique idea. It is the responsibility of the designers and managers of both undergraduate and postgraduate courses and training to make it possible for such people to flourish, or at least not obstruct them unnecessarily.

The Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History aims to celebrate Queensland’s medical history by telling the stories of its people, events, objects, scandals and triumphs. We welcome all stories with a medical history aspect. Get in touch with us at medmuseum@uq.edu.au.