Profit and self-promotion in medicine

Misguided and useless operations and treatments are ubiquitous and have always been part of medical and customary healers’ practice. Primarily such treatments are delivered in good faith, with mistaken but sincerely held beliefs and a desire to relieve suffering. A charlatan, however, is by definition a health practitioner who uses their position to gain either reputation or profit. I have used objects from the collection to illustrate examples of such behaviour.

Discriminating between the misguided and the fraudulent inevitably is a balancing act and the author is responsible for the value judgements it entails. I am particularly wary of judging the past through our contemporary knowledge, values and world views but ethical issues do not change over time.

Distinguishing a practitioner who is self-promoting but practising ethically contrasts with a charlatan, who delivers treatments which they know are of little use or even harmful, by using clever advertising and spin (the word charlatan comes from the Italian word to chatter). Usually, the practitioner’s professional qualifications are less than stated or bogus and the treatment is more quackery than based on verifiable research. The range of the misrepresentation reveals a spectrum from outright lies to overgeneralisations and partial truths. The “chatter” plays on our ever-present decision-making biases. Confirmation bias is prominent when the procedure uses a long-held belief and recency bias comes to the fore when an idea seems cutting edge. This is supported by herd mentality bias when the subject only uses a confirming source. Testaments can be of great importance whether it is from a Roman Emperor, a social media influencer or a successful celebrity, but also can occur when the promoters of a treatment claim expertise in a subject about which their target has little knowledge. A modern twist is the misplaced self-confidence and sense of exceptionalism which we are encouraged to prioritise over the advice of qualified professionals. An unknowing public has always been vulnerable to such practitioners who often may be convinced by their own skill and ideas but later, to maintain an inflated reputation, ignore evidence of failure and often work outside established medical practice.

Uvular scissors

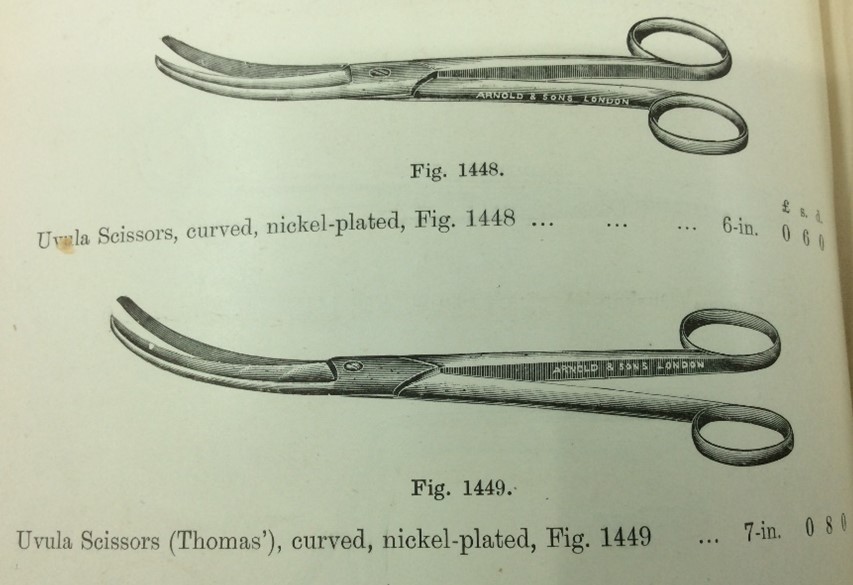

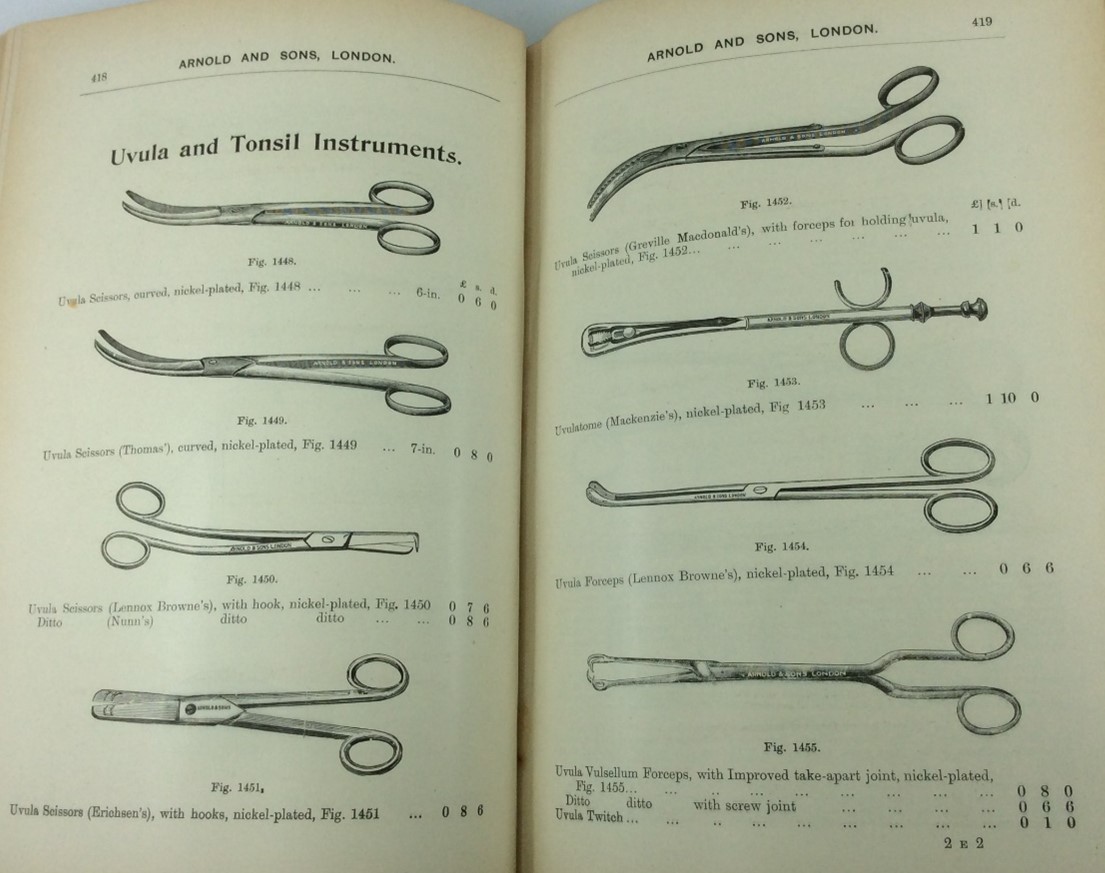

This article arose from finding a pair of uvular scissors whilst reviewing a box of instruments in the collection. These may have been used to remove the uvula in people complaining of pharyngeal discomfort, but why? There was a period for a few years around 1840 of exuberant claims for surgery. Correspondence in the Lancet in 1841 reports Dieffenbach’s operation on resecting the base of the tongue to relieve the muscle spasm he thought caused stuttering. He retracted his hypothesis but others later claimed simply removing the uvula was helpful. These operations were soon discredited but not before many had been carried out without benefit.

Uvula Scissors and Forceps from Arnold’s Catalogue circa 1904.

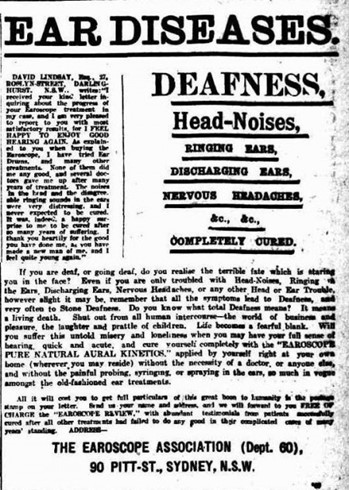

Earoscope

An Earoscope in the Marks-Hirschfeld collection added to the intruige. A newspaper article found online claimed this carefully crafted instrument enabled anyone to cure all aural ailments simply by regular use at home, seemingly the epitome of charlatanism. This instrument contains a diaphragm that sends a pulse of air into the external meatus, however details are hard to come by, and the Earoscope is sealed so as to keep its mechanism secret.

Phrenology

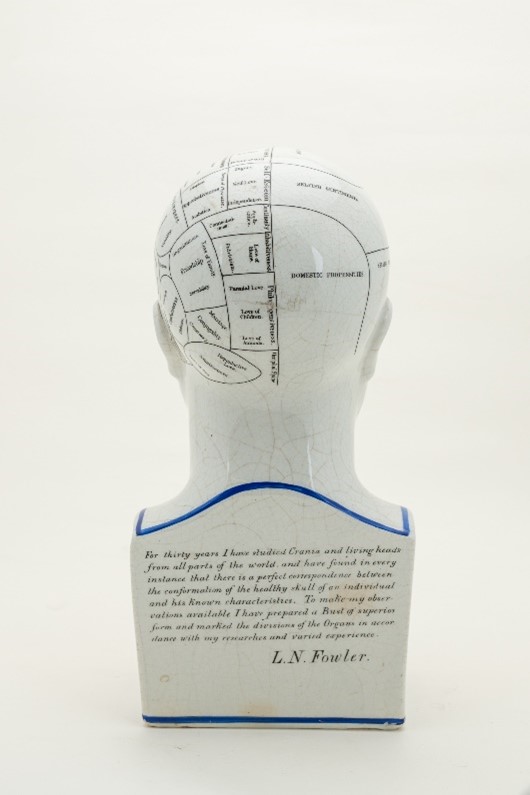

Phrenology, derived from the ancient Greek art of physiognomy or character assessment from facial appearance, was another misguided and dangerous idea which became popular in the 18th Century. Later, Sir Francis Galton, the English polymath and social Darwinist, together with an Italian, Cesare Lombroso applied their “scientific” reasoning to support views of society, based on eugenics. They used a series of extracranial measurements and observations including photographs to not only determine the origins of disease and personality but also the patients’ criminality and racial origins. These ideas tick all the boxes of charlatanism, but they were promoted by an otherwise respected scientist. It is likely that the Museum’s glazed pottery cranial model, marked out with phrenology areas, is a recent 1960s reproduction due to the large hole in the base from the modern process of slip casting:

Phrenology Model from the MHMMH Collection: The Inscription reads: “For thirty years I have studied Crania and living heads from all Parts of the world and have found in every instance there is a perfect correspondence between the conformation of the living skull of an individual and his Known characteristics. To make my observations available I have prepared a Bust of superior forms and marked the divisions of the Organs in accordance with my researches and varied experience. L.N. Fowler”

The Fowler brothers Orson and Lorenzo were from New York. They heard of phrenology through books by Andrew and George Coombes who founded The Phrenology Society of Edinburgh in 1820 and saw the opportunity for profit. Throughout the 19th Century phrenology was treated as a serious science by many. The ideas persisted due to slick salesmanship and supported the racist, determinist and religious prejudices of the times. It is an example of how a false idea can be as serious as an operation or useless prescription.

Disgarded treatments

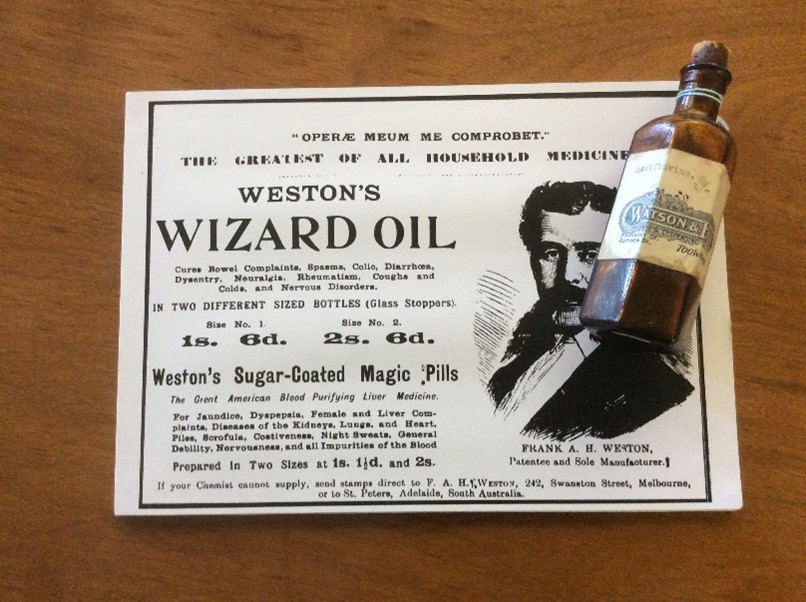

Many long discarded recommended treatments for various ailments have found their way into the Museum collection. Advertising by proponents was extensive and is illustrated below by a few examples:

Electrical stimulating probes

The Museum collection contains several sets of electrical stimulating probes. Electrical treatment has fascinated practitioners and sufferers for many years, and such a powerful, invisible force is an ideal candidate for those who wish to profit from an elaborate ’modern’ therapy but few examples of efficacy exist. It was particularly used in the treatment of neurasthenia when the muscle stimulation obtained seem to support it as a useful treatment for tired, floppy muscles. A similar looking instrument is displayed on level three in the Mayne Building, but it is a UV light generator and would have no more benefit than the electric stimulator pictured below. Furthermore, it has the potential if overused to be harmful.

Organ displacements

A diagnosis of organ displacements has been used for inexplicable ailments for centuries as in ‘hysteria’ being caused by the wandering uterus. More recently, prior to IVF, corrective surgery was offered for retroversion and anteversion of the uterus for infertility, but fertility is unaffected by these variations.

After the introduction of contrast media, diagnostic radiology was used to ‘validate’ dropped stomach and dropped kidneys by the appearance on Barium swallow of a stomach lying in the pelvis or a kidney on a pedicle appearing displaced. There was strong confirmation bias to accept these anatomical variations as a cause of unpleasant symptoms. My introduction to the problem was in 1974 when an elderly woman showed me the stomach tube with which she had performed weekly auto-gastric lavage since 1935 when she had been told this would relieve her dyspepsia which was caused by her ‘dropped stomach’! The distal five centimetres were almost detached, and she wondered whether I could get her a replacement?

Diagnosis of dropped kidney or nephroptosis, was first made in 1885 and ‘dropped or floating kidneys’ have been treated with surgery (nephropexy) to correct this variant. Always controversial, it seems likely that this idea was substantially supported from this use of Xray imaging from mid-1894 onwards. It is rarely necessary except when renal dysfunction can be demonstrated such as ureteric obstruction and has significant morbidity and even fatality associated with the procedure. To accuse practitioners using these treatments of being charlatans requires a knowledge of intention. This cannot often be ascertained. However, following a marked decline in incidence over many years, a recent study reports the use of modern techniques but is short on detail of the patients selected for this procedure [International Braz J Urol Vol. 36 (1): 10-17, January - February, 2010 Jonas Wadstrom, Michael Haggman assess the use of laparoscopic nephropexy]. Editorial comment draws attention to the limitations of this small study with only 12 months follow up and concludes with a caution this statement; “For all those (mobile kidneys), which produce urinary obstruction and those with a beginning dilation, nephropexy still has an efficient justification and may–correctly performed–give much blessings”. Nothing needs to be added to this statement of Professor Voelcker from Halle in the year 1911.

Purification

Blood letting, laxatives, emetics, enemas, colonic lavage, have arisen from Galenic ideas on the purification of bad humours and seamlessly fit into folklore cures. Each have application to modern scientific medicine but have been used unethically. Colonic lavage was popular up to the 1930s and except for ensuring an empty bowel as preparation for endoscopy or bowel imaging now has little benefit to health except as a precursor to bowel retraining after extreme constipation. However, there are some beautiful brass enema sets in the collection from the 19th century which suggests their use by fashionable practitioners.

Irradiation

X-irradiation both diagnostic and therapeutic has been used by unscrupulous practitioners since its introduction. Early machines were available in Brisbane for entertainment in the early 1900s and later to determine correct shoe sizing. What now seems questionable practice was widespread by practitioners who were unaware of the risks, using hand-held applicators in treatments accepted by everyone. Irradiation, radium and thorium for skin blemishes were used in excess in the 1920s until their damaging effect was recognised much later. Irradiation for other inflammatory conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis was normalised. My father received this treatment c.1948 which he said helped him greatly and did not result in any induced neoplasia or other injury.

Chelation therapy

Chelation therapy with intravenous deferoxamine has been used to reduce iatrogenic iron overload in some patients with haemolytic anaemias after receiving multiple transfusions. A similar procedure can be used for arsenic, copper, lead and mercury. However, its use by some practitioners for detoxification programs to treat heart disease, strokes, autism and nonspecific chronic ill health without established evidence of metal overload has been denounced by various authorities such as the Mayo Clinic and the American Psychiatric Association. It seems dangerous to those who appreciate the risks entailed but remains available and advertised in Brisbane. Although specific warnings are listed, it reflects our present preoccupation with contamination and pollution, and has some proponents, though some cases would seem to come under the category of charlatanism.

Toxic materials

The widespread use of toxic materials up until the modern era and continued press articles about problems with different but potent chemicals and microplastics may be the fear that is being relieved by such, albeit ineffective, treatments. With reference to past iatrogenic injury, the 128 items in the materia medica box produced by Evans Lescher and Webb in our collection includes many metals such as arsenic, antimony and mercury salt, with a wide selection of herbs, flavours and thickeners. Only about 10% would be recognised as having any positive therapeutic use, such as the cinchona bark containing quinine, the raw opium for morphine derivatives, belladonna for atropine, ergot mould for ergotamine, ferrous sulphate, colchicine and possibly zinc sulphate for skin eruptions, potassium iodide (anti-septic), ipecacuanha (emetic), senna (laxative) and podophyllin for warts.

I have compiled a by no means comprehensive list of some of the more problematic uses for which such medicines have been prescribed in the 20th century.

Zinc inhalation for influenza was promoted on all troop ships returning soldiers to Australia in 1919 to the extent that the supplies of zinc sulphate ran out. It is useless and required special cabins for its compulsory administration on troop ships, but the army medical services were persuaded of its efficacy. (AMJ-Special Report by MRC 1921)

Teething powders with mercury were widely sold in the 1930s until they were associated with a debilitating and occasionally fatal childhood condition named ‘pink disease’ (Infantile Acrodynia), due to mercury poisoning.

Cough suppressants are consistently found to be of no therapeutic assistance in acute respiratory infections and are potentially deleterious due to sputum retention and impaired ventilation. However, they relieve a patient’s distress and are still sold in large quantities.

Anti-diarrhoea medicines using opiates, kaolin or gut motility reducing agents have little or no effect on the serious effects of diarrhoea, particularly in infants.

Tonics especially, nux vomica (strychnine), bitters, gentian extracts, hypophosphates and thyroid gland extract have been provided by apothecaries, chemists and doctors since the professions have existed and used to make up a substantial part of standard pharmacopoeias.

Bex and Vincents tablets (Aspirin, Phenacetin and Caffeine or APC) were easy to obtain as a cheap “pick me up”. Commonly promoted by word of mouth they were widely used in the community by women caught between the pressures of domesticity and economic demands on families in the 1950s and 60s. It has taken a public health program and restriction on sales to reduce their use because of their association with renal papillary necrosis from compound analgesic overuse especially fuelled by the addictive potential of caffeine. Who is responsible: the promotors such as images of the ‘ideal home’, health professionals or the manufacturers who profit from the sales of these medicines? The care with which these products have been presented (taste colour, smell and not least packaging) to the hapless users who often copped the most blame. Before congratulating ourselves that we have put such nonsense behind us we should consider the vast range of nutritional supplements now sold in chemists with almost no support from scientific study, except in very few cases where there is a demonstrable deficiency, to a population who have better food available to them than ever. Where do these fit on the charlatan, misguided or useless spectrum? I suggest that they supply the need for the healer to provide something and the patient to receive care and attention: is this charlatanism, or a harmless example of kindness, or marketing exercise to maintain income and contact with a regular customer, or the result of a patient centred demand? Possibly it is all of the above.

Supporting a particular religious or political regime

From a broader political and religious perspective there is the potential for supporting a particular religious or political regime. The King’s Evil was a common disease, scrofula or tuberculosis of the skin, which had the reputation of only being cured by the monarch’s touch–a case of royal charlatanism? The process also supported the absolute power of a monarch. Faith healing in, at least, Christianity, is well based in the biblical accounts of the capacity for healing shown by Jesus. So, appealing to God within a faith context is rational to the believer. However, those whose faith is not rewarded especially if the intermediaries have profited by their attempt, are damaged by the practice. To avoid personal bias in this account, I would add that the borders between malpractice negligence and unacceptable risk-taking are often not clear cut. Issues around high incidence of iatrogenesis and the control of health being commandeered by the medical profession and the highly profitable health industry are well documented and blaming the patient for failures continues unabated.

As a final consideration, the discussion is complicated by the presence of both placebo (and nocebo) effects. If the patient feels better (or worse) following treatment but the results are not reproducible in an appropriate therapeutic trial, what occurs is well described as “mind over matter”. If presented with full disclosure, this is not a problem but can be if it is used for undue profit or has potentially serious side effects. Fifty years ago, a study from the South of England [Thomas KB; 1978: The Consultation and the Therapeutic Illusion. BMJ 1(6123):1372-1328] showed that in unselected patients presenting to a general practice who felt ill, about one third had a diagnoseable disease with an effective treatment; one third had a diagnoseable self-limiting disorder; and one third complained of symptoms which were not diagnoseable as a recognised disorder. It is not surprising that many treatments have been developed to cater for these people, but it is a group who are vulnerable to the charms of charlatans or over interventionist health practitioners.