Advances in medical science has repeatedly led to misguided or useless medical practice

As pointed out in Newsletter No 80, misguided and useless operations and treatments are ubiquitous. The persistence of these practices long after they have been shown to ineffective is difficult to explain, except by the conservatism and unwillingness inherent in human behaviour and justified by the limitations of personal experience. I thought this warranted a return to the subject.

Popular and professional understandings of disease and its relationship to religion, philosophy, politics, economics and social structures underpin our attitudes to ill-health and the acceptance of these treatments. Since the overturning of tradition and religious belief, the basis for managing illnesses by experimental proof has been the standard for the acceptance of an effective treatment when it has been validated by peers who include the elite of medical establishment and the approval of their institutions and disinterested centres of excellence in universities, but it is the interpretation of the results which determines our conclusions. Often the target audience has insufficient knowledge or expertise to critically assess the claims especially when it answers the search for cure by what seems a rational or easy solution, or one that fits their world view. There has been a continued paradoxical reluctance to relinquish the magic, folk lore and eccentric beliefs in the quest for an elixir of life to overcome all diseases, and so the mixed and often contradictory messages regarding health information continue.

Much of medical practice has in hindsight been shown to be both more dangerous and less effective than its practitioners would have us believe when it is introduced. Both doctors and patients are desperate to find cures and have been guilty sometimes of overenthusiastically taking up the theme that “anything is worth a try” when nothing seems to be effective. Several items in the Marks-Hirschfeld Museum collection reflect this.

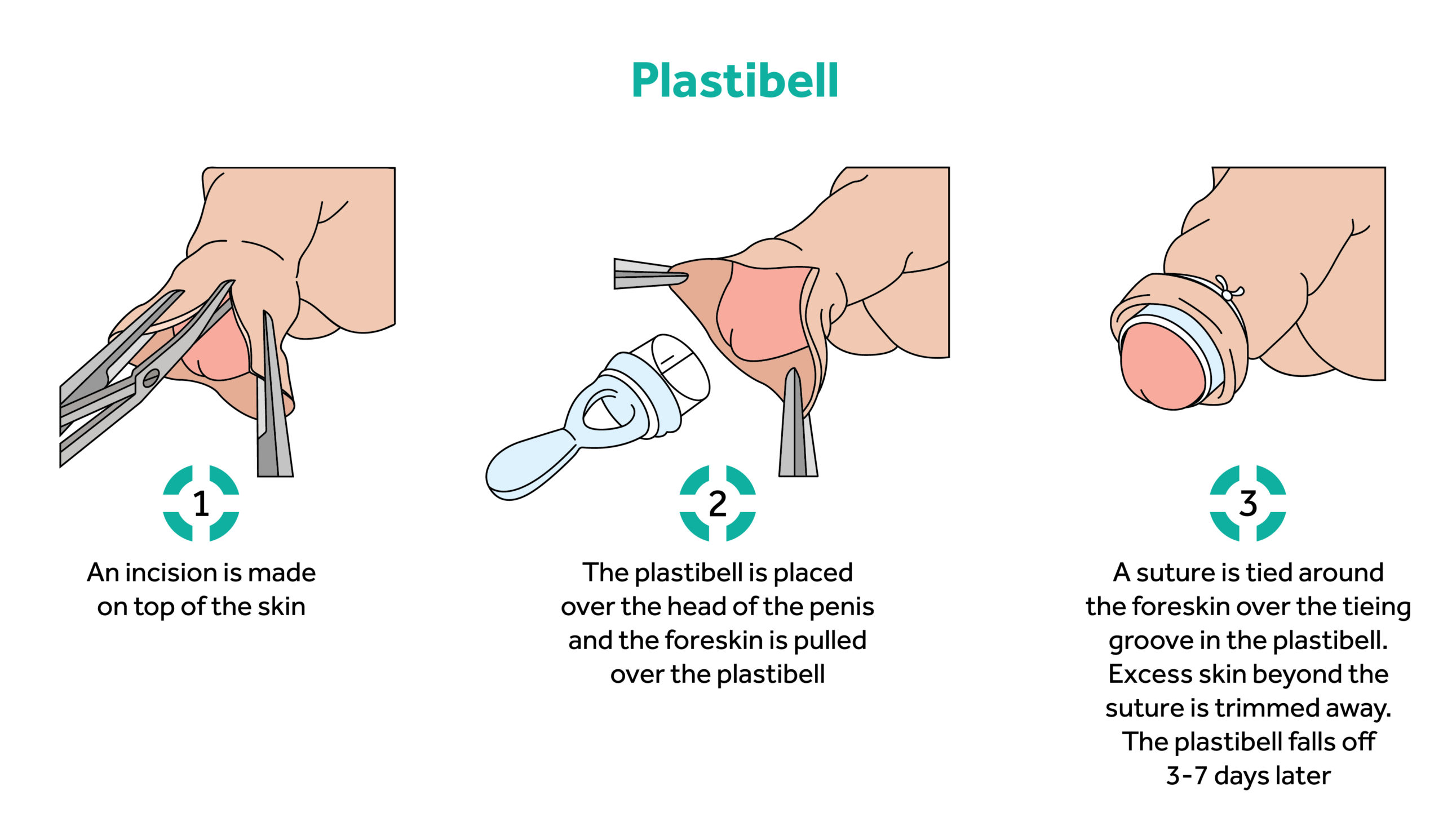

The uvula scissors and information about the operations designed to treat stuttering (outlined in the last newsletter), reminded me of hearing about attempts to cure delay in speech and speech impediments by incising the lingual frenulum because it was thought to restrict the development of these skills and diagnosed as tongue-tie. Winston Churchill was subjected to this procedure. Often male circumcision was carried out for cultural/religious reasons as there is only the occasional case of severe phimosis when it could be reasonably claimed to be necessary, but the hygienists of the early 20th century popularised it without admitting the significant rate of serious mishaps for what appears to be a simple cosmetic procedure. These complications, such as damage to the urethra, are reduced using methods such as the Plastibel but the procedure is almost always unnecessary and maintaining good hygiene is all that is needed to prevent chronic balanitis which rarely has led to malignant change. Examination of the basis for these treatments shows the difficulties of separating malpractice from acceptable evaluation of a contemporary treatment.

Gum cutting lancets and blood letting instruments were discussed in another recent newsletter. Similarly, dental clearances for the purpose of treating systemic disease, especially arthritis, gained popularity when the treatment of gum disease without antibiotics was unsuccessful. Unfortunately, it was recommended for untreatable systemic disorders without benefit to the patient. In his discussion of autointoxication, a contributor to William Osler’s Modern Medicine 1937 (of which there is a facsimile copy in the Marks-Hirschfeld Museum collection) there is reference to cryptogenic sepsis causing various ailments including ulcerative endocarditis and pernicious anaemia and halitosis. These conditions were correlated with Pyorrhoea Alveolaris in a way that could easily be interpreted as cause or chance rather than effect and dental treatment including extraction was recommended (vol V; pp41 and 54-56).

Prior to the development of effective diuretics (firstly mersalyl as an injection and then oral chlorothiazide) Southey’s Tubes were fine tubes inserted subcutaneously into the calf tissues to reduce oedema in the commonly occurring dropsy associated with chronic renal, hepatic and cardiac failure. The effect would be satisfying to observe the watery fluid running out and the oedema subsiding with elevation and bandaging but utterly ineffective for treating the underlying condition. It was also harmful due the significant protein depletion’ let alone the risk of life-threatening cellulitis with the introduction of bacteria into the fragile skin.

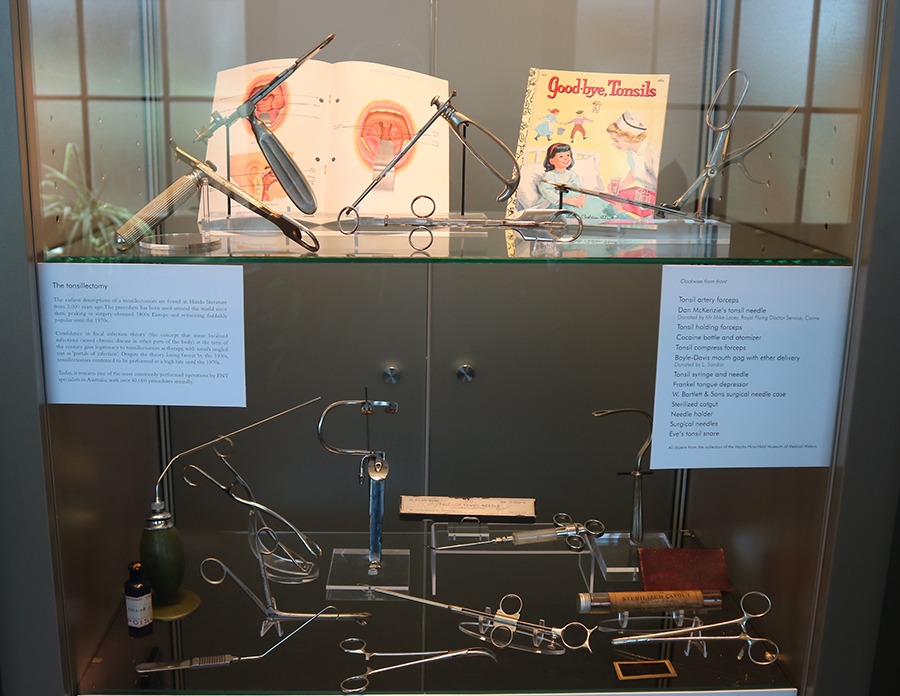

Tonsillectomy snares and guillotines are plentiful in the Museum collection and indicate the high frequency of tonsillectomy. Until the advances of recent years in our understanding of immunology the importance of tonsils, appendices and other collections of lymphatic tissue in the gut, spleen and lymph nodes were therefore deemed to be unneeded for health and so excised as expertise in surgical practice developed. This occurred with the increasing use of tracheostomy for diphtheria and the apparent success of the removal of scarred and swollen tonsils leading to ENT surgeons gaining confidence in their skills of in this operative field. It was a short step to the increase rates of tonsillectomy because it could be done, and it almost became a rite of passage for well cared for children! There are indications for chronically damaged tonsils to be removed but not without considering the risks of such surgery and the requirement for anaesthesia which inevitably might threaten the airway. This is an example of another situation where, because it was possible, the procedure was done to excess.

The story of tonsils applies to appendix, until recently considered an unnecessary anatomical throw-back to a ‘more primitive’ stage of development. Until the late 19th surgery most doctors tried hard to avoid abdominal surgery. Hippocrates disallowed ethical physicians to ‘cut for the stone’, and a wish to avoid surgery often distinguishes physicians from surgeons to today. Just prior to his coronation King Edward VII was seriously ill with appendicitis. Frederick Treves, the Sergeant -Surgeon, successfully operated to drain an appendix abscess, which was well publicised and so ensured confidence in such surgery. It probably did not become a readily accepted procedure until after 1945 with the advent of safer anaesthesia and antibiotics, when the operation became a common treatment for chronic and acute abdominal pain. Often it was performed for mesenteric adenitis (swollen lymph nodes in the gut associated with any intestinal inflammation). Like tonsillectomy the operation is safe enough and lifesaving, when necessary, but now is performed much less frequently when imaging pre-operatively reduces the risk of misdiagnosis and unnecessary surgery.

In addition, as is evident in the collection’s Evans, Lescher and Webb Materia Medica Box, until about 1950, much of commonly prescribed medication was misguided, useless or dangerous. This applied especially to heavy metal products (though arsenicals had proved partially effective in treating syphilis by 1900 and antimony had a place in treating some bacterial zoonoses). The multitude of tonics prescribed for what we would now label mild depression and anxiety were of doubtful use other than as a placebo.

After the discovery of the pathophysiology of the absorption of vitamin B12 in pernicious anaemia and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, the use of injections of cobalamin as a ‘nerve tonic’ for neurasthenic patients became common. It is an example of the generalisation of a scientific finding to a “might as well try treatment” with the added advantage of the mystique of an injection. There is a similar story regarding thyroxin which until recently continued to be occasionally recommended as an adjuvant to antidepressants in euthyroid patients.

Controversial areas persist in the use of hypnosis, aversion therapy and some other forms of psychological as well as physical therapies however it is incumbent on the practitioners to be scrupulous in the testing of these therapies and this has not always been so. Regulators must be aware of a practitioner’s potential to unduly influence their customers and patients and to continue to be sure the treatment is working, and they have not fallen into the trap of misunderstanding that the distress of stopping an ingrained habitual practice is not misattributed to the return of the illness for which it has been given. They are also obliged to assess any harmful effects resulting from the therapy which in the case of homeopathy, reflexology and other non-invasive treatments are unlikely. Acupuncture receives many claims and particularly combined with moxibustion could be considered riskier if the traditional form of deep insertion is performed, but by far the most serious unwanted iatrogenic damage is caused by conventional medical interventions.

There must always be an awareness for the possibility of dismissing an effective therapy due to its misuse or overuse. Acupuncture can be effective for pain and the minimisation of withdrawal symptoms on stopping addictive drugs though its use in a wide variety of other conditions is contentious. Relief from withdrawal symptoms following cessation of cocaine and opiates was well documented in studies carried out at the University of Hong Kong in the 1970s and has been confirmed in many studies since either alone or in combination with opiate agonists. Magnetic therapy would seem to be an extension of electrical therapy and has been sold to relieve muscle and joint pain but for the most part has been dismissed by established medical opinion. Recently, using considerably stronger magnetic fields its effect on polarising and depolarising ions in individual cells has been used in the medical imaging (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and to induce seizures as in ECT to attempt to avoid some of the side effects of this procedure, especially the amnesia which is often of short duration if the number of seizures is kept to a minimum. With these two I examples I emphasise the importance of keeping an open mind.

The Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History aims to celebrate Queensland’s medical history by telling the stories of its people, events, objects, scandals and triumphs. We welcome all stories with a medical history aspect. Get in touch with us at medmuseum@uq.edu.au.