Memories of another era

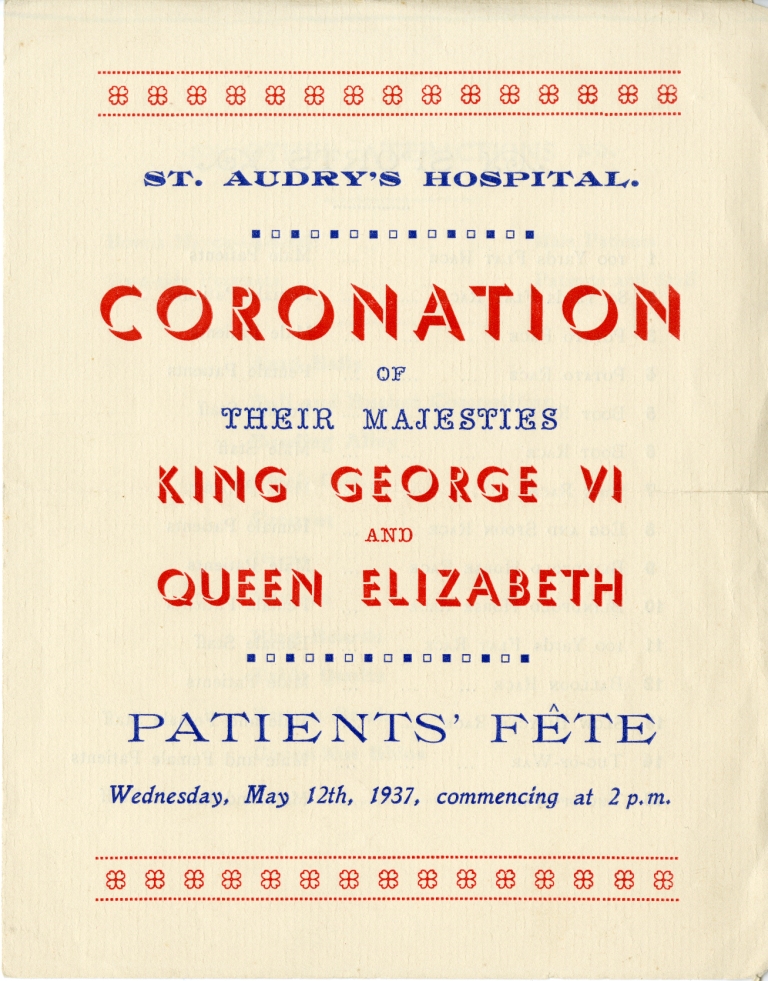

In 1964, having left school at 18 with a university place to study medicine, I was given the opportunity to work as an assistant nurse for three months in a large residential mental hospital in Suffolk, England. The job was meagrely paid but board and lodging were included in a nursing home for single students and a few other older nurses. Suffolk was a poor rural county and renowned for its parsimonious treatment of the services which legislation required the county council to provide. Mental health services were not an exception but after 1948 the hospital came under the National Health Service Regional Health Authority, though it still seemed as though that there was never enough money for improvements. This experience was available to me by virtue of my medical student status and was hugely beneficial after a privileged upbringing and, for the most part, a private boarding education to get such close contact with everyday life before entering the somewhat privileged precincts of Cambridge University. In the long term, the time I spent giving personal nursing care to a wide range of people, all of whom were deprived of liberty and in a less than comfortable situation, became even more influential. The hospital buildings were very old, built in 1765 as a workhouse dating from the Poor Laws to deal with vagrants and the impoverished from the time of Elizabeth 1st. With several extensions, it had become the County Asylum for Lunatics from 1827 and in 1916 was renamed as a Hospital for Mental Diseases.

An enduring memory was the New Year’s Eve ball attended by many staff, patients, Board members and their families. The hospital housed approximately 2,000 patients and probably employed as many as 1000 nurses and other health staff (such as a dentist, social workers, anaesthetist, pathologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, hairdresser and barber) in addition to the many others needed to run such a substantial estate as an almost self-sufficient enclave. It meant apprenticeships for staff, including gardeners, engineers (steam, refrigeration and mechanical), builders and other many other tradesmen, which in turn meant training for many patients.

Most of the wards were locked routinely, though only the male and female admission and acute wards maintained strict security. Male and female patients lived in separate wards and staffing for each retained this gender separation. There were no junior doctors, and the few psychiatrists and medical officers had a low profile. I had the impression that the senior nurses were the permanent fixture and ran the hospital. There was a hospital secretary with minimal secretarial support but little other in the way of administrative staff. The hospital was close to a small town and there was transgenerational employment for many in an almost closed society. This was the era when the Chief Nursing Officer and Matron ruled. The two World Wars had terminated the previous period when doctors (often labelled alienists) had been supreme when so many were called away on military duty, but before the administrators gained control in an increasingly bureaucratised health service.

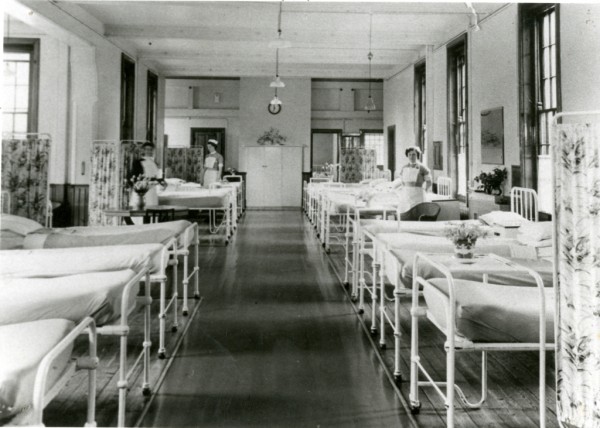

A feature of mental hospital design of the period was the long corridors, intended as a security measure. These connected the wards and other buildings, giving rise to a claustrophobic and closed in atmosphere. The wards were all the same design: a large day room separated from an even larger dormitory of up to 100 beds, close packed with two central double rows and single rows at the sides each with a small personal bedside cupboard. At the far end was the charge nurse’s (or sister’s) office flanked by about four single rooms with furniture secured to the floor, which served as seclusion and observation rooms. Off the dormitory was a large bathroom with three or four unscreened baths and numerous washbasins. Alongside the dayroom was a kitchen with steam heated containers for the food which was delivered from a central kitchen and served in the dayroom. The meals served were palatable and in fact often enough for the staff meals after the patients had been fed. Cutlery was boxed and counted on return to the kitchen. As another suicide prevention measure all windows were securely barred. Hospitalisation has never prevented suicide attempts and I have found it surprising and distressing that the immediate weeks after discharge remain a high-risk period.

One of my jobs was bed-making after breakfast. Usually with another student nurse this meant 50 beds apiece, with attention to neatness and regularity. After this I was usually told to accompany patients to work (such as occupational therapy or work groups attached to the hospital) for which they received small sums of money. At that time pensions, sick and unemployment benefit were not paid to hospitalised psychiatric patients, so unless they had other savings this was the money needed for tobacco, toiletries, personal items and clothes. The latter were provided if the patient couldn’t afford them, but a constant complaint was the damage done by laundering and lost items, so all patients ended up with dishevelled and ill-fitting clothing. ‘No work: no pay’ was the order of the day, except for a few exemptions due to ill health. Another of my work allocations was to play cribbage with a pleasant elderly man who had independent means. My recollection was that we played for threepence a hand and so I quickly learnt how to play and have enjoyed the game ever since.

Bathing and shaving were afternoon activities for those deemed unsafe to be left to do this themselves, which included several of the patients I cared for, either because of incompetence or suicide risk. I was not informed about diagnoses but did not always require explicit explanation: Florid psychosis (e.g. demanding to be called Napoleon by a bed ridden imposing old man suffering GPI (general paralysis of the insane from tertiary syphilis—a common diagnosis in the hospital); severe depression (with melancholic withdrawal) and marked intellectual disability which was frequent though complicated by developmental trauma and poor education. Bathing grown men and even more so shaving them with the added risk of scraping the skin—electric razors were not provided—made for quite a learning curve but also taught me the empathy and sympathy derived from such close human contact.

Electro Convulsive Therapy was carried out in the dormitory area about twice a week for probably a dozen patients using inhalational anaesthesia by a visiting anaesthetist and certainly a visible seizure was obtained. I don’t remember any accidents or problems occurring, but I am sure like elsewhere at this time, ECT treatment was used too often, ineffectually and often leaving unnecessary memory loss. However, I have a lasting memory of witnessing a middle-aged farmer being admitted with severe melancholic depression, almost without speech, expression or movements and after three treatments he had recovered to his usual self. On one occasion deep sleep therapy had been recommended which was carried out in an observation room with a nurse in constant attendance, Sleep was induced for, I think, 72 hours or so with amylobarbital repeated when signs of waking occurred. However, this procedure was uncommon, and I understood it to be a somewhat of a last resort for unremitting psychotic depression. Up until a few years earlier insulin coma was used but proved even more dangerous. Paraldehyde mixed with fruit juice, with its distinctive smell, was the usual sedative and given in shot glasses before dinner. This ritual earned the name ‘cocktail time’ and was seemingly relished by the recipients. I’ve never forgotten the smell and was given a taste which I can still recall after nearly 60 years! I’ve also not forgotten seeing how painful it was as an intra-muscular injection which was the usual sedation for out-of-control psychosis on admission to hospital. Chlorpromazine had only recently been introduced and maybe was deemed unreliable—circumstances would have made IV injections difficult; but use of the aversive effect of paraldehyde was probably in play as well.

Violence on the ward was uncommon but always close at hand (not only against staff but also between patients and I was reliable informed just as problematic in the female wards). I was told on arrival NEVER to turn my back to a patient. Notably, the only time I’ve been assaulted by a psychiatric patient was as a psychiatric registrar, in an outpatient clinic in Stanthorpe many years later, when I thought the consultation had finished, I dropped my gaze to write notes and the patient leapt over the desk with fists flying. Luckily, he had no weapon. In 1964, junior nurses were on the chronic wards for night duty. I was not asked to do this but as far as I know there was only one nurse, and the wards were locked with no key provided to the on-duty nurse. Using the safety provided by other patients for his or her protection and time to get help proved more effective and safer than measures which could encourage more conflict through weaponizing a confrontation or having keys in the ward.

Occupational therapy was taken seriously and in various forms. The art and crafts sections were extensive and therapeutic. The industrial section took on outside orders for woodwork and particularly fabric work and such things as sock making, even if occasionally a lack of supervision led to mistakes—such as when somebody in charge of the sock maker decided not to include the heel in its program. The workshops and studio were run by qualified craftsmen with nursing staff always available. For the most part it seemed as though it was appreciated by the patients and gave pattern to their lives, with the possibility of rehabilitative qualities and the token payment introduced a reward for effort. Most patients stayed for long periods in hospital and sometimes for life. Stories of a few being born in the hospital were told to me but I never encountered such a resident, and it is probably more likely that they would have been made a ward of the state. Many long stay residents were abandoned by their relatives. A story was related to me that on one occasion when a resident had a significant win on the football pools plenty of visitors arrived! Whilst working at Baillie Henderson Hospital in Toowoomba I participated in a project to contact ‘lost’ relatives and it was clear that they had often in the past been discouraged or even refused permission to visit, but reinstituting contact was not always successful.

This experience has been unforgettable. At the time I decided that the job tended to make for highly eccentric psychiatrists and chose to take up general practice. After coming to Australia when nearly 50, I decided to join the psychiatry training scheme and worked at both what was Wolston Park Hospital and Baillie Henderson Hospital as well as other acute mental health units in Brisbane and Toowoomba. The two older hospitals were opened in the same era as Saint Audrey’s in Suffolk. Unlike the acute units in general hospitals, I was constantly reminded of my earlier experience by staff and patients alike. Nostalgia can be negative, but I greatly value the experience and often wonder if we have been too quick to dismiss asylum as a valid therapy for chronic mental illness, especially if we consider how cheaply it was provided in the past and what a difference extra financial support could make to a modern equivalent. The number of people with poorly or untreated serious mental disorders ending up in prison or homeless is clear evidence of an ongoing gap in our service provision.

Further reading: For more detailed accounts of the themes to which I’ve alluded, I’d recommend John Cawte’s The Last of the Lunatics from his experiences from the 1950s in Adelaide. Melbourne University Press, 1998.

This article was also published in a shortened form by Hektoen International; A Journal of Medical Humanities in October 2021

The Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History aims to celebrate Queensland’s medical history by telling the stories of its people, events, objects, scandals and triumphs. We welcome all stories with a medical history aspect. Get in touch with us at medmuseum@uq.edu.au.