Digital drugs are a phenomenon about which little is known. The consumption of digital drugs involves listening to binaural beats - sound which is claimed to mimic the experience of psychoactive drugs, or to elicit specific cognitive or emotional states, often while using ingestible psychoactive substances at the same time. But how common is this practice, and who is using digital drugs, and why? These are the questions our team of researchers from the Global Drug Survey (GDS) aimed to find out through an exploratory analysis of data.

What are binaural beats?

Binaural beats have grown in popularity in recent times, but biophysicists have been exploring the phenomenon since the 1970s. Binaural beats are created when two tones of slightly different frequency are presented to each ear separately, and at the same time. For example, if you are listening to a 440 Hz tone with your left ear and a 444 Hz tone with your right ear, you would perceive a modulating chord with an audible “beat” of 4 Hz (cycles per second). This beat is claimed to “entrain” brain waves and incite cognitive and mental effects; in some cases, mimicking the embodied experience of psychoactive drugs.

Research investigating binaural beats has found that listening to these sounds may result in pain alleviation, anxiety reduction, and improved memory, but findings are mixed around its effects on concentration. However, there is very limited research exploring the extent to which people listen to binaural beats as a substitute for using psychoactive substances, or in conjunction with psychoactive substances to enhance their effects.

The study

The Global Drug Survey (GDS) – now in its 11th year – is an annual, online, anonymous survey undertaken by people from around the world who use any form of drugs. In 2021, the survey included a brief series of questions related to people’s engagement with binaural beats. They asked how often and for how long people engaged with binaural beats, why they used binaural beats and how they accessed binaural beats. Notwithstanding, we also captured a lot of information about people’s other drug use as well (from cocaine to cannabis, alcohol to ayahuasca, prescription opioids to microdosing and everything in between).

What did this study find?

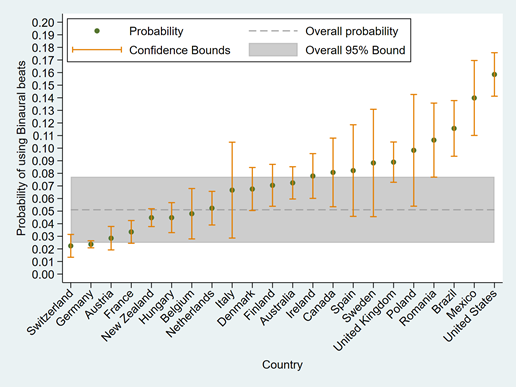

In total, 1,635 people (5.3 per cent of the total sample of 30,896 people) reported using binaural beats to experience altered states in the last 12 months. These people were younger and more likely to report recent use of all other drugs (including cannabis), compared with the rest of the sample.

The highest rates of using binaural beats were reported among respondents from the United States, Mexico, Brazil, Poland, Romania, and the United Kingdom, with Australian respondents ranking 11th.

Most people listened to binaural beats did so on a median of 10 days in the past 12 months, so roughly once a month. People most commonly listened to binaural beat content through video streaming sites, Spotify and other app-based services.

Why did people use binaural beats?

Many respondents described using them “to relax or fall asleep” (72.2 per cent) and “to change my mood” (34.7 per cent), while 11.7 per cent reported that they were trying “to get a similar effect to that of other drugs”. Other respondents said they were using binaural beats to increase concentration, focus or productivity, for meditation or spiritual practices, to ease headaches or pain, and to facilitate lucid dreaming, astral projection and other “out of body” experiences. Others reported use of binaural beats to enhance experiences with psychoactive drugs, for example “to help relax when using drugs like psilocybin which can create meditative states” and “while smoking DMT”.

What does it mean?

This study provides scoping information about the phenomenon of binaural beats, demonstrating that some binaural beat consumers aim to connect with a higher consciousness (“something bigger than myself”), and some report listening to binaural beats to obtain similar effects to psychoactive substances, while others report listening to them while also taking substances, in particular psychedelics. The mere existence of this phenomenon challenges broadly held assumptions about what drugs actually are. For example, what constitutes a psychoactive effect, and what constitutes a psychoactive substance?

Authors

Dr Monica J. Barratt, Social and Global Studies Centre and Digital Ethnography Research Centre, RMIT University; National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW.

Dr Cheneal Puljević, Centre for Health Services Research; Centre of Research Excellence on Achieving the Tobacco Endgame, School of Public Health, The University of Queensland

Dr Lachlan Goold, School of Business and Creative Industries, University of the Sunshine Coast

Associate Professor Jason A. Ferris, Centre for Health Services Research, The University of Queensland