Ruminations on teething

Teething has always been a fascination to mothers, and their medical or traditional advisors. The process generally occurs with the milk teeth (usually twenty small and less differentiated teeth) erupting between six months and twenty-four months of age. This is a period of maximum risk in the infant’s life. Infant morbidity is universal and mortality (0-5years) has been estimated at 40% in eighteenth century England compared with something like 0.2% in Australia and up to 25% in poor third world malarious countries today. This age cohort includes the dangers arising from birth, the developmental milestones of weaning, increased mobility, autonomy and social exploration; exposure to infections including gastro-intestinal disturbances and accidents during a period when the infant is still completely dependent on the care of others. Inevitably mistaken correlations were made as to cause and effect and in mid-sixteenth century a French surgeon Ambroise Paré wrote an influential and well published account of his habit of cutting the gums of infants who became ill at the time of teething, supposedly derived from his understanding of the cause of death from a necropsy. The medicalisation of this condition invaded the realm of older remedies of blistering, cautery of the back of the head and even leeches on the gums. Over the next four centuries much was written usually defending painful interventions. However, William Cadogan (1711-1797 wrote in “Essay upon Nursing” of his empirical observations that teething was natural and harmless and usually proceeded without untoward danger.

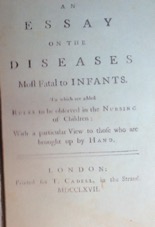

On pages 74-87 in Armstrong’s 1767* “An Essay on the Diseases Most Fatal to Infants”, it is quite clear he supports William Cadogan’s view as he quotes verbatim his argument for accepting the harmless developmental natural history of teething. He nowhere recommends lancing the gums. If the infant is ill his usual mantra of administering a laxative and a ‘puke’ are suggested. Many of Armstrong’s contemporaries were enthusiastic gum cutters. A Lancet article from 1996** on the history of the gum-lancet found that John Hunter would carry out the procedure repeatedly and Joseph Hurlock reputedly advocated gum lancing in every childhood disease whether teething or not. However, by mid nineteenth century with slow reduction in infant mortality it became clear to many that teething did not cause serious disease, but old habits die slowly. On the basis of ”better to be safe than sorry” Charles West, founder of Great Ormond Street hospital continued to advise gum lancing even though he believed it to be “a perfectly natural process”. By 1884, when in other areas of surgical practice intervention had become more acceptable a meeting of the Medical Society of London suggested “leeches and the lancet should lie in the same dark tomb”, however opinion was divided, and most participants disagreed with Edmund Owen a surgeon from the Hospital for Sick Children who was reported to make this remark. They were convinced “lancing prevented diarrhoea and convulsions caused by teething”.

However, the practice continued to decline, and Abraham Jacobi in New York, who was by then drawing attention to the social factors that underlay many paediatric conditions, noted it had lost most of its charms. But teething remained a disease in many minds. Paediatricians in 1918 asserted it could cause diarrhoea, vomiting, catarrh, convulsions, screaming fits and strabismus. A recommendation to consult a dentist as to whether lancing gums should be considered was found in a textbook as late as 1938. There is not a single report of complications arising from this procedure and most doctors, whatever their opinion as to its effect, seemed to have shared John Hunter’s view that lancing was never attended by dangerous consequences.

Few now would ascribe anything but mild discomfort to teething though a baby’s disgruntlement, sleep disturbance and susceptibility to infection is often blamed on it. However, proprietary medicine, usually mildly sedating, are common on Pharmacists shelves in order to mitigate its effects. Variation of the usual developmental sequence and timing continue to surprise with occasional occurrence of three sets of teeth or an erupted tooth being found at birth, but nobody is likely to attribute these to witchcraft or magical intervention, and we no longer have the spectre of a total teeth extraction being performed to remove the focus of infection deemed to be the cause of rheumatic disease as was common in 1930s. In our present culture devoted to ‘selfies’, teeth are probably valued for their influence on our appearance (especially given their showing our age) more than their functionality and our disposable expenditure is more likely to be directed to cosmetic improvement.

*George Armstrong; An Essay on the Diseases Most Fatal to Infants: London; 1767;

Published by T Cadell, The Strand, London.

**The Lancet and the Gum-Lancet: 400 Years of Teething Babies; The Lancet; Vol 348;

December 21/28, 1996