Rotten teeth in order strung: Advertising and the ethical dentist

Second instalment of articles from the Museum of Dentistry (MoD) established by the ADAQ, looking at the advertising practices of early Queensland dentists.

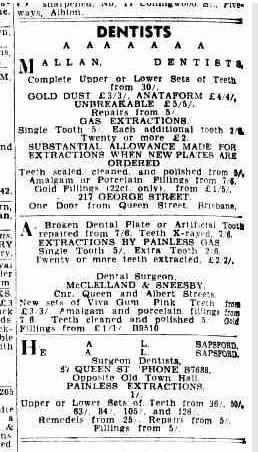

Today, dental practices are regulated health services and must follow AHPRA’s guidelines for advertising. In Queensland, dentistry remained unregulated until 1901, therefore anyone could claim to practice and promote their services. The main selling point was painless and affordable tooth extraction through chloroform, ether or laughing gas.

Restrictions became necessary to stem the activity of unscrupulous tooth pullers and to create a fair ground for the duly qualified and ethical dentists who advanced the professional standing of their field. In the early days of travelling quacks and barber-surgeons, Western dentistry really just involved gruesome extractions.

A popular way to advertise dental work to illiterate customers was to hang pails of blood and teeth strung together.The black and white bands of the barber pole still hint at these cups lined with red rags.

His pole with pewter basons hung

Black rotten teeth in order strung.

Rang’d cups, that in the window stood,

Lin’d with red rags to look like blood.

John Gay, Fable 22. (1700s)

As late as the 19th century, dentists continued to display dentures, extracted teeth and their tools, such as tooth keys, as a way to show their skills to prospective patients.

Dentures for sale

With easily available anaesthetics and the advent of more affordable vulcanite dentures, unscrupulous practitioners would advertise the economic advantages of having all teeth removed and replaced by false teeth. In the early days of European settlement, many Queenslanders were scammed into extractions of healthy teeth, because: “…wholesale extractions with vulcanite plates pay well” (Odontological Society of Queensland minutes).

It’s not surprising that the recent excavation of the North Brisbane Burial Grounds revealed many edentulous skulls. The only treatment available to most was visiting the surgeon appointed to the Colonial Medical Service, or a meeting with a shady tooth extractor.

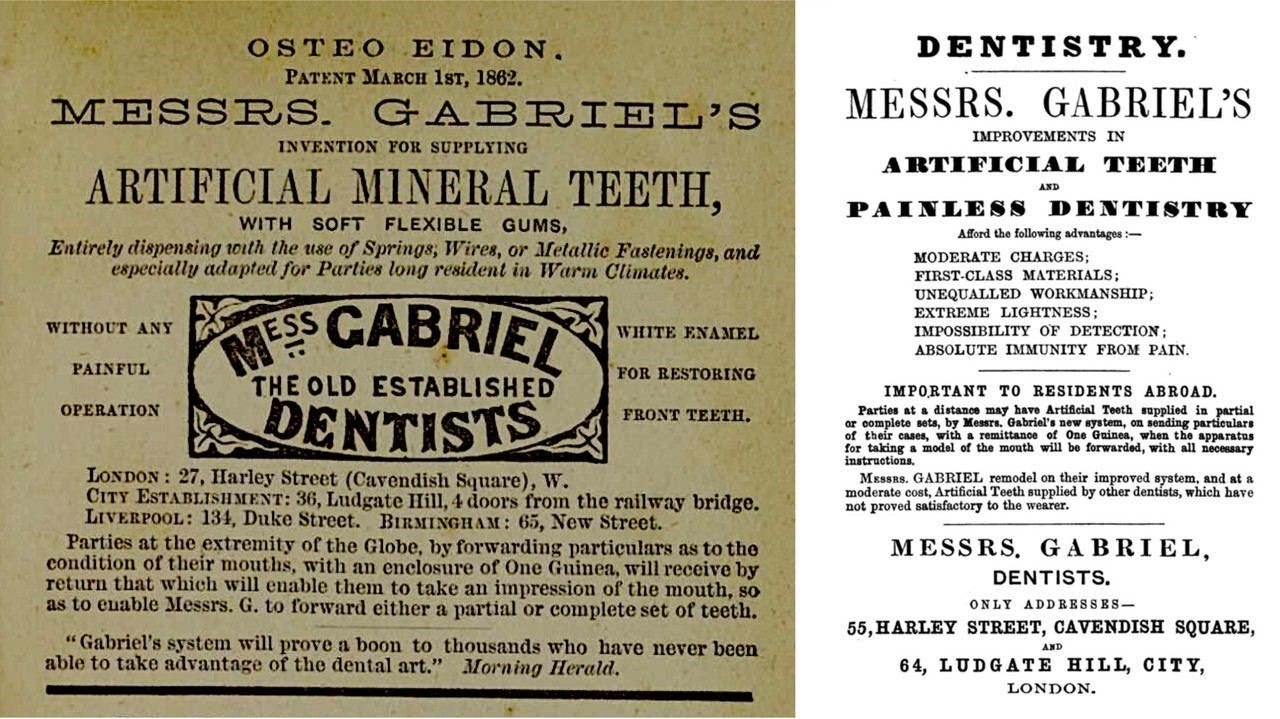

The first Brisbane-made dentures appeared around 1854. Dentures were often advertised as available for sale through mail order from London. In some cases, used denture plates were re-sold at discounted prices to the very poor.

As dentistry began to be recognised as a health profession in Britain, many qualified dentists, armed with their new Licence of Dental Surgery – as awarded by the medical school - bravely relocated to the antipodean colonies and set up private practice. These young professionals often travelled around the state, advertising in the local paper where and when they would be available for consultation, often at the local hotel or pub.

The ethical dentist does not advertise

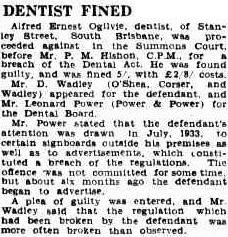

Queensland’s Dental Act 1901 defined dentistry quite poorly, so dodgy tooth pullers continued their practices until the 1920s legally, as long as they did not use the word: dentist in their advert.

The Odontological Society of Queensland fought bitterly against the shameful advertising of most extravagant and unethical claims by charlatans that stole their patients, and thus their livelihoods. The fight took the shape of advocacy for regulation and recognised university qualifications became the main weapon. The other weapon was drafting a Code of Ethics for the profession, that heavily restricted advertising.

The minutes of the Society meetings show some lively debates about the ills and shames of advertising dental work. Supporters argued that advertisers were useful to patients who could not go to a dentist and pay ordinary fees. However, they were ostracised by those who found it unsafe, undignified, and immoral to advertise surgical procedures as commodities open for bartering:

“We as dentists are working on the human subject performing surgical operations, therefore any slovenliness on our part will endanger the health and life of the individual … Other communities in other parts of the world realise this and are raising their standard of health which means raising their standard of dentistry. Italy for example requires that a dentist first graduate in Medicine…” (ADAQ Archives)

We don’t name and shame, but the Americans did: the famous Painless Parker personified the advertising dentist as ‘menace to the dignity of the profession’, according to the American Dental Association. Accused of false advertisement, he went so far as to legally change his first name to Painless and kept going!

Nevertheless, Parker is today seen as a pioneer of the chain dentistry business and, in his own twisted way, of public oral health education. The Historical Dental Museum at the Temple University School of Dentistry exhibits a display dedicated to Parker, with his necklace of 357 carious teeth and a large wooden bucket filled to the brim with teeth he had pulled.

In 1912, the Council of the National Dental Association of Australia agreed on a Code of Ethics that clearly distinguished the ethical dental practitioners from the quacks still populating the streets. According to this early Code, the dentist:

“…shall not exhibit or permit the display in connection with his name or practice in any window, shop or show case open to public inspection, any dental specimen, appliance, apparatus or professional card.” Furthermore: “He shall not allow his name to appear on dentifrices, toothbrushes, or proprietary articles”.

Unfair advantage

However, these ethical concerns weren’t directed to street tooth pullers alone. The 1936 draft text for the new ADAQ Code of Ethics shows that the rules also ensured a level playfield and no unfair advantages among the tight-knit group of member practitioners who drafted it, many of whom resided in the areas and competed for the same pool of wealthy patients!

The allowed signage for the premises was heavily regulated. Moreover:

“Any announcements by way of:

- Public hoardings

- Advertising spaces

- Theatre and Picture theatre screens without the approval of the Council

- Programmes and tickets of all kinds

- Dodgers and circulars, or any printed or written matter for circulation among the public MUST BE AVOIDED.”

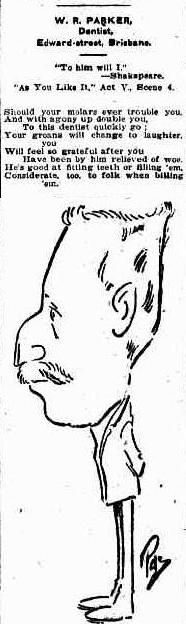

With such strict restrictions, even the most prominent Queensland practitioners looked for ways to circumvent them, such as using the social pages rather than classifieds. This perhaps compares to today’s social media posts?

The 1930s Code of Ethics is however a lot closer to the wording of today’s AHPRA guidelines for advertising health services.

Today, while unfair and unprofessional competition remains, the emphasis of ethical advertising is on the importance of not being misleading or deceptive for the benefit of the prospective patients’ health and wellbeing.

The Marks-Hirschfeld Museum of Medical History aims to celebrate Queensland’s medical history by telling the stories of its people, events, objects, scandals and triumphs. We welcome all stories with a medical history aspect. Get in touch with us at medmuseum@uq.edu.au.